World Of Networks.

When in Paris, a visit to Centre Pompidou is a must. And it really delivered for me on this occasion. There was no pre-planning so it was all a surprise and a superb way to spend a few hours on an early Friday evening.

The main focus was on a collective exhibition entitled, "Worlds of Networks", which brought together 60 artists, architects and designers who question the place of the network in our societies, and whether in fact, everything has become a network these days.

“At a time of environmental crisis, the first network is also that of living things, where humans give themselves in coexistence with other species.”

Lessons from footwear.

Before I got up to this floor, I was already taken by a shed filled with trays of mosses. On closer inspection it was a beautiful study, from Gérard Hauray, of the way strangers transport living organisms on their body. They collected samples from the footwear of visitors to Centre Pompidou and cultivated them in trays in accordance with botanical engineer Claude Figureau’s elaborate procedure.

What resulted were examples of trees, mosses, ferns, flowering plants and cyanobacteria. Unfortunately the plaques were all in French so I couldn’t read up on the stories, but each visitor had explained their location and purpose I think, so it could be possible to marry up (or not) these proto-landscapes.

World of networks.

On with the main exhibition.

What is shown here is my takings from it, rather than the exhibit as a whole. This is simply because it was huge, with a lot to take in, and I rather spend time admiring and questioning the mediums that appeal most to me - like textiles - so I guess, I potentially miss out on the context of the show this way, and only give focus to that which I already know. I was also concerned photos weren’t allowed, so I made minimal notes on what I deemed as important to me, yet then saw others taking photos and invigilators not caring. Subsequently I have given an overview of the show segments with some pieced-together thoughts, and expanded on what I captured most of.

Global network.

This section looked at the timeline of networks becoming artistically expressed. It started in the year 1690 with an anatomical drawing, then up to the year 2021 with digital networks as the focus.

Above ground: How do we access and utilise the networks around us? How have people-places been designed so that they flow, are comfortable - or perhaps, they haven’t been designed in this way and so are not accessible. There were some pages showing from A Pattern Language - Towns, Buildings, Construction by Sara Ishikawa, Christopher Alexander and Murray Silverstein, that considers a ‘language’ of formal design considerations, like the height of a windowsill or where villages would be situated to benefit all.

Ground: In a wider consideration, Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion Map is the only flat map of the entire surface of the Earth, which reveals our planet as one island in one ocean, without any visually obvious distortion of the relative shapes and sizes of the land areas and without splitting the continents. Fuller was one of many to recognize how maps shape our worldview, policy and decisions, and so this map aimed to equip humanity with a better tool to address existential challenges and systems interventions.

Below ground: So that’s above ground, but what about below? Also shown was the “wood wide web” as it’s now being called - the network of mycorrhizae that allow trees, plants and fungi to interact and support one another in a symbiotic relationship.

Critique of networks.

The digital networks that appeared in the 21st Century enabled the rise of surveillance and censorship, and in an era of dependence on such networks, new infrastructures are easily implemented to observe and control. In the beginning, the Internet was seen as emancipating; giving freedom and increasing global connectivity. It was an age of information never before experienced, and so quickly received too. So this section of the exhibition addressed concerns and feelings of entrapment in response to these supposed open networks.

1. Intertwined: Created using cables bound with copper, Alice Anderson shows Internet Cables, a twisted hanging of heaviness; the intrusive and gnarly connectedness of the digital age. What I didn’t realise from this installation, is that in fact the artist conducts dance performances using objects such as this, which further brings to life the uncertain path this network is taking.

2. Emotional: Machine learning allows real time data collection of anything. Shown here, Mika Tajima’s Human Synth is a digital smokestack of human emotion as collected through Twitter trends, giving shape and creating collections of strangers’ comments. Gjertrud Hals’ Vena Cuprum (2018) is a visualisation of the living and non-living intersecting, using blood vessels as the base yet creating them in iron and copper wire.

3. Extraction: Katja Trinkwalder and Pia-Marie Stute’s Accessories For The Paranoid (2017) are four prototypes devices that manipulate our domestic surveillance systems, like webcams, Alexa devices and search engines. In Simon Denny’s Centralization vs Decentralization Hardware Display: Fujitsu/Bitcoin/GoL 1978 (2018), board game Game Of Life is connected to a decentralised Internet network (i.e. pre-current networks) so that Bitcoins can be generated, making a statement on the extractive processes our networks now allow - both for the equipment and the outcomes.

4. Inequity: By mapping the Earth from Space, we’ve been able to document and identify so much information not readily available beforehand. In this collective work from Diller Scofidio, Laura Kurgan, Robert Gerard Pietrusko and the Columbia Center for Spatial Research, the team were able to observe and reveal the scale of unequal distribution of infrastructure relating to light. While spatial mapping allows us to feel connected - like with Fuller’s Dymaxion Map above - it also highlights inequities through the sheer lack of something, like light. Below you can watch the full video, In Plain Sight (2018).

Knots and reticulations.

The place for textiles seems obvious when conjuring up an image of the word “knot”, for we imagine the tightening of rope. Even to envisage the intertwining of intestines when we’re nervous, or discombobulating neural pathways when confused - as in, “to tie oneself in knots” - have this sense of tangibility. According to the exhibition, the word “network” appeared for the first time in the 12th century to designate a net or a knot, and from this grew examples of textiles as an explanation for the intricacy of networks. This section then was really what got me hot and bothered, as it were.

1. Physical connection, invisible traces:

First up, Richard Vijgen with WifiTapestry 2.0 (2021), a tapestry embedded with thermal elements that converts wireless signals emitted in the space into electrical currents that move through the weave. Actually, I wasn’t connected to Wifi and so this could be the reason I didn’t see anything occur! But the electrical currents heat the wire, which then change colour so creating a connection to the global networks that allow Wifi, with an almost invisible trace of you being there (because it isn’t recorded).

Next, Tomás Saraceno’s Solitary social mapping of DDO / 78 by a solo Nephila senegalensis- one week and a duet of Cyrtophora citricola- two weeks, (2017). These two Latin names refer to spider species. Further research on the artist’s website leads me to understand that the spiders were monitored over a period of 7 days, then the web treated with ink and “cosmic dust” before being fixed to archival paper. Usually an ephemeral and transient affair - a near invisible trace of the spider’s passing - the complexity and differences in the spiders’ webs now offers up a physical connection.

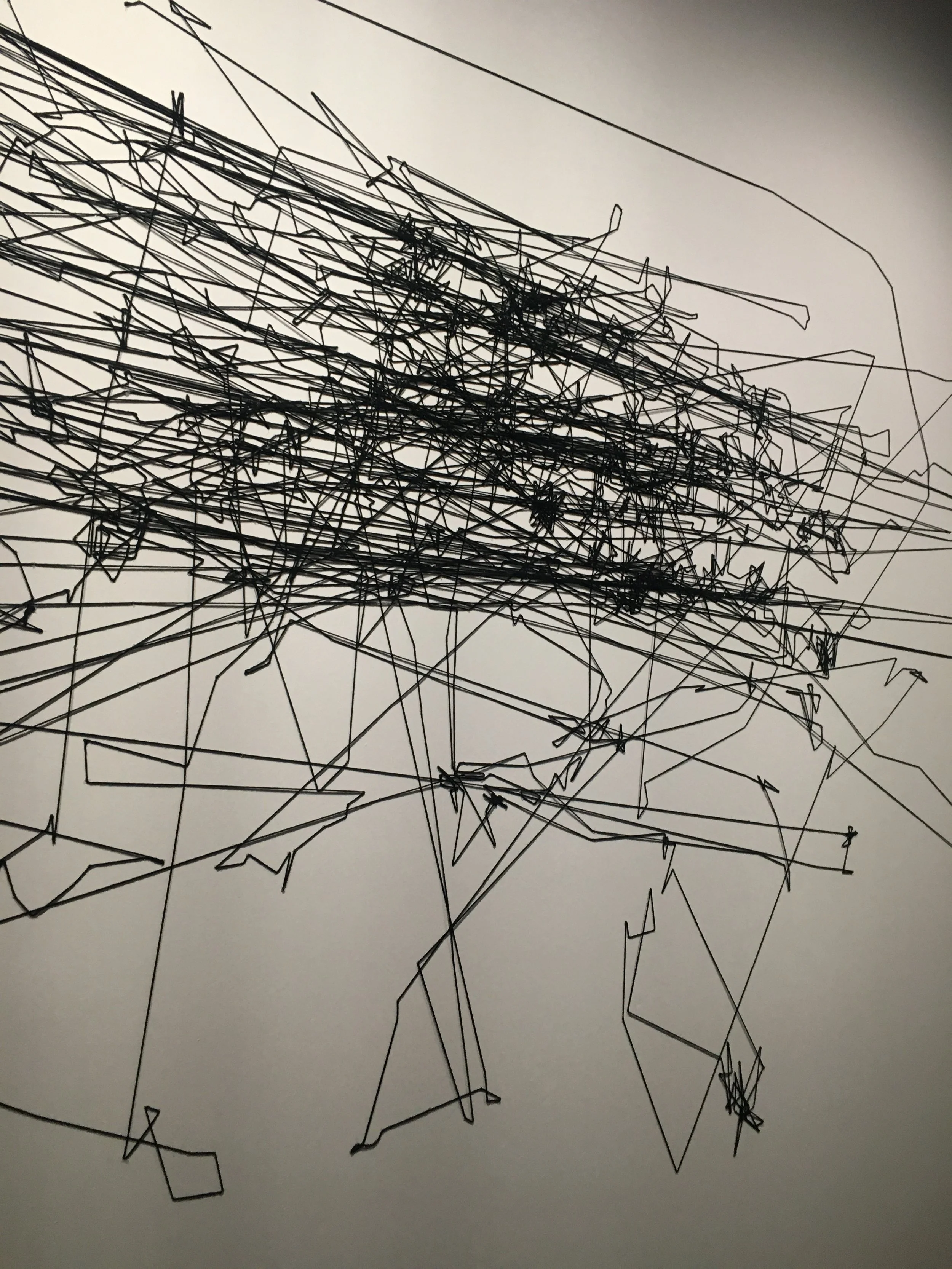

In Anthologie des regards (Regard de Brian Price sur le film Patterns of Life), artist Julien Prévieux offers a potentially voyeuristic notion of networks; the tracking of our inner thoughts via eye movements. What catches our attention? He tracked someone watching one of his films, and used woollen yarn against the wall to showcase these “ghostly glances”.

And then a medley of works, including: František Lesák’s A tree camoflagued as a tree (1972), a photograph of a tree covered completely in camoflague fabric (far right of the image), and Yona Friedman’s Ville spatiale (1959), a metal model of a city raised up on planes (very bottom left) that would allow for reconfiguration for assets like electricity and a new vantage point. Here the networks are more about our connection; how we navigate a space affects our perception and familiarity, and often we miss important features.

2. Tangible connection from everyday fibres:

Even behind a glass case, there are certain materials that we can easily understand and build understanding of as they are in our everyday, such as cotton, wool, leather, plastic. And despite a woven fabric not screaming “network”, it is a path nevertheless - especially when you consider the supply chain.

The first image shows Sheila Hicks’ Drizzle (1988) made with linen yarn, and in image three another Hicks work, Prayer Rug (1972-73), both of which were simple yet complex, exploring simple knotting techniques and undyed natural fibres. Then a historic sample in image two, that has been identified as cotton and wool, which looks to be to be a sort of loincloth based on the shape, again simple and complex simultaneously, this time because of a smocking technique and use of two shades.

The black board was pinned with various playful examples of weaving with standard and non-standard materials. It was captivating. Created by Helle Jongerius, 3D Weaving Research Objects (2019) showcased chunky ropes sewn through webbing, paper weaves, rope and paper blends, simple backstap loom weave, macramé, couched rope, hand-stitched paper… all of this appealed to me as I explored rope during my MA, as a signifying material for the place I grew up. Again, simple yet complex. You create a woven fabric from one shade and one fibre (like Sheila Hicks above in image 3) and it is extravagant up close, yet as soon as you start to play with colour, scale and materials, it becomes less of an everyday. Is it any less comforting? It is more fragile because of the paper? Is it more “arty” because it seems to have been designed for aesthetics rather than purpose?

Interestingly, this is what the purpose of the research was! To question the craft of weaving in an age of disposable fabrics. The JongeriusLab collectively worked on these in situ weaves, addressing the tactile dimensions of textiles and their place in cultural innovation.

3. Shifting conventions:

From far away, Samuel Tomatis’ Alga - Vannerie (2017-2021), looks to be potentially plastic, maybe leather, there’s some wood, some fish skin looking bits. In fact, it’s algae. Accompanied by a team of multi-disciplinary scientists, Tomatis was able to explore the transformation of an invasive algal species into a productive industrial material. Though there are clear functional uses for such a material, like packaging, Tomatis has worked with traditional artists in Guadeloupe for their skill in knotting, braiding and weaving, to create beautiful objects from organic waste that still operate functionally.

The living network.

This section considered the symbiosis of all living organisms, and how they are both interdependent yet part of a wider network, for instance flocks of birds, and mycelium.

Images 1-2: ecoLogicStudio Physarum City Drawing (2021). Physarum polycephalum is a unicellular organism (all life processes, such as reproduction, feeding, digestion, and excretion, occur in one cell) that is studied for its capacity to learn and communicate. For this exhibition, the studio considered how technological and biological intelligence could co-exist and communicate, to explore how we can learn from biological sources to better plan our urban spaces. They installed a Generative Adversarial Network algorithm (some sort of machine learning) that would read and assess Paris’ urban structure through the behaviour and perceptions of this organism. The description was all too technical for me, but the imagery and microscopic video was fascinating.

You can learn more about it in this article here from www.floornature.com and see a video of the machine learning-organism exploring Venice.

Image 3: Trevor Paglen Cloud #135 Hough Lines (2019). Through investigative work, this artist has been exploring how governments and private enterprises perceive air space - apparently, these systems are unable to comprehend cloud masses. The lines on the image shown are the networks - the line of sight - of different artificial intelligence facial recognition programmes.

Image 4: Jenna Sutela nimiia cétïï (2018). Visits to museums and galleries can merge into one if the themes are similar, and on this occasion of writing up thoughts months later, I had reckoned I’d seen this work at Nottingham Contemporary. In fact, I’d seen something from the same artist that was related to this piece, but at the time didn’t make the connection. A real jaunty audio-visual piece that explores the possibility of natural and synthetic life forms interacting, with similarities to ecoLogicStudio above in the use of bacterial intelligence. AI’s automatic learning ability (machine learning) was used to create a new collectively-achieved language via the movements from Bacillus subtilis (an extremophilic bacterium), Martian language poems (?) and a network of artificial neurons. Head to the blog link as shown for a video of this haunting work.

Images 5-6: Studio Formafantasma Cambio (2021) and Quercus (2020). I’d come across this studio at the Waste-Age exhibition at the Design Museum; playful, grand. This piece was just as fun yet poignant, and could easily sit within a Natural History museum setting as an educative warning (in fact, the objects come from Paris’ own xylotheque).

Cambio focusses on the extraction, production and distribution of wood products, and highlights here a small collection from the colonial periods to mass-industry. Alongside it, the video Quercus has a tongue-in-cheek script read by “the forest” questioning an alternative to the extractive methods seen today in timber felling. I found myself nodding along in acceptance of what the trees were saying us humans consider them as, and what they reckon an alternative could be.

Head to the Studio Formafantasma site for more images of the growing exhibition and research, along with the Quercus video in full.

So that’s it.

Super lengthy “review” of an exhibition. The curated themes and corresponding works were diverse so as to appeal to everyone, and to both simply and complexly showcase the spread of networks - they essentially answered their question of whether living things should be the first network to consider; as seen through the works above, even when tech was utilised, the network still had a living element.

Plus: Moving about the space was easy, it wasn’t overcrowded, and everything was displayed for easy contemplation and reading. This continues in the rest of the museum, and it really makes a difference to enjoyment when you have the space and time to immerse yourself. Of course, this isn’t all the works that were on show, but the ones that appealed to my values and practice. If you want to dive in, you can watch short videos from some artists on the Centre Pompidou site.