Threads of Change.

Threads of Change was a five-day festival of panel talks, workshops and an exhibition hosted at London’s Nehru Centre by Khadi London. Building on the Festival of Natural Fibres of previous years, this event brought together folk to continue examining how transformative change of the textile and fashion industries could occur.

Each day established particular themes. I only made it to day two — Climate Change and Social Justice. Though I want to highlight discussions from this visit, they’re going to come in additional posts because the exhibition itself presented too much to talk about. This article therefore is about the exhibition only.

To read about the previous exhibition and discussions, head to my lengthy write-up of 2022.

Exhibition.

The Nehru Centre acts as the cultural wing of The High Commission of India in the UK, and both supported this year’s festival in providing a space to exhibit. In 2022 it was hosted at Craft Central, also an interesting building with high ceilings (and frankly both venues annoying to get to; this one in particular as we had to go to Mayfair where income disparity is incredibly clear). The light space allowed the works on show to breathe.

Where 2022 felt more of a trade show with some exhibitors having stands, this was displayed as an exhibit with outfits and wall hangings hung up, and a vast table of artefacts. The only area that seemed set up to do business of any sort was Raddis, though perhaps the opening night had more of that talk. Instead I was able to silently muse over everything.

Threads of Change.

A festival celebrating the transformative opportunities in regenerative fibres and economies for the textiles and fashion industries.

Ashna Patel + Marianne Noer.

‘From Near Not Far’ is a project that investigates craftsmanship and locality through cultivating wearables from local natural fibres in Denmark such as raw Danish wool, Nordic wool yarn and European linen. This is a ten-piece collection that was made over five months by the duo, that looks back at Danish heritage, exploring folkwear and craft techniques including hands-inning, handweaving, dyeing and wet felting. The pieces on show are a tunic, pair of trousers and a vest. The vest was probably my most favourite piece from the whole exhibition for its chunky simplicity and tactility.

Cate Victoria + Resham Dor / Baby Yak CAAD.

Resham Dor is a brand that is reviving the Kharad craft cluster in Kutch, Gujarat producing flooring textiles from local wool (‘kharad' refers to ‘spreading on the floor’). The panel on show with sweet motifs is woven using native camel wool.

Baby Yak CAAD is a cooperative situated in the Mongolian province of Arkhangai, initiated by the French NGO AVSF. This area comprises of 298 families and 1490 herders who are experiencing desertification and effects of climate change, so this coop offers a sustainable income by encouraging them to rear yaks instead of goats. A local value chain is created as the herders process their own wool and craft products, rather than immediately shipping fibres to urban centres for processing. The yak wool shawl was probably very soft, but we couldn’t touch any of the items!

The Colour Caravan + Sanja Stories.

These two separate pieces represent a commitment to fostering and promoting traditional craftsmanship to ensure the sustainability (preservation) of knowledge.

The Heritage Border Cape from The Colour Caravan is designed, handspun, handwoven and hand sewn by artisans located in the Kullu valley of Himachal Pradesh from indigenous sheep wool. The border is inspired by a traditional regional dress (Kinnauri pattu). Swati Seth founded The Colour Caravan as a social enterprise to foster economic progress for women artisans and shepherds of the region, using these products as a means to revive native wool and local skills.

The cream jeans are made from an unbleached and undyed raw regenerative khadi cotton. Designed in collaboration between a handful of folk, these jeans represent an alternative collaborative business model; Sanja Stories Denim is comprised of Rachel Sheila Kan (Ecosystem Incubator), Jo Salter (Where Does It Come From?), Kishore Shah (Khadi London), Abhishek Jain (Mishika Crafts) and Claudia Coveyduck (Sample Studio). The style is designed in a way that allows for adjustability and repair through replaceable knee pads and a drawstring waist. I’m not convinced they’re all that adjustable because there are darts and a fly with button, and saying the height is adjustable because of roll-up legs feels unnecessary (this is more of a styling feature as all jeans can be hemmed — check out Blackhorse Lane Ateliers for this service) but they are a nice straightforward pair of trousers.

Images: 1. Ashna Patel + Marianne Noer ‘From Near Not Far’ outfit of trousers, tunic and vest tied with rope; 2. Cate Victoria and Resham Dor camel wool woven kharad panel, and Baby Yak CAAD yak wool woven shawl; 3. Processed yak wool fibre; 4. Photos of yak herders in Arkhangai province, Mongolia; 5. The Colour Caravan Heritage Border Cape made from indigenous Western Himalayas sheep wool and Sanja Stories Denim collaborative unbleached undyed regenerative cotton twill trousers.

Saumya Singh.

‘Aeggis’ is a woven panel using an eggshell ceramic ‘yarn’ within the weft of an otherwise British wool weave. It is an attempt at “redefining the cyclical approach” of material consumption, and highlights farm stories. I imagine that the weave is fragile, just as eggshells are, adding to the transience or ephemerality of this piece.

Kitty Carlton-Smith x Khamir.

Weaver Kitty explored khadi during her time at Chelsea College of Arts (I think because of a competition set by Khadi London), diving into the legacy of Gandhi alongside a love of yoga. She worked with Gujarat-based craft organisation Khamir to create yoga mats using the kharad technique. Kharad looms can be easily set up and moved throughout the desert and so are well-suited to nomadic tribes, though this craft is no longer as widely practiced. Kitty then offers a new interpretation; the circles and lines, plus tonalities of the natural colours, presents an opportunity to align with both the flow practice of yoga and the flow practice of handicrafts.

Sarah Tibbles x Gramin Vikas Pratisthan.

Another Chelsea textiles student, Sarah explored ‘forest silk’ with the artisan weavers in Chhattisgarh (part of Gramin Vikas Pratisthan). Having specialised in woven textiles, she designed a panel encompassing diamond motifs and gradating stripes that revealed natural textures and colours of the undyed silk fibre. Forest silk is also known as eri silk, and is spun from living moths that break th cocoon when they emerge, so creating a shorter fibre. The cocoon is affected by local climatic conditions and the original silkworm’s diet, and this creates uniques hues.

Images: 1-2. Saumya Singh ‘Aeggis’ woven panel of British wool and eggshell ceramic; 3-4. Kitty Carlton-Smith’s two kharad yoga mats made in partnership with artisans of Khamir; 5. Sarah Tibbles’ forest silk woven panel made by artisans of Gramin Vikas Pratisthan.

PICO.

PICO work with various artisan clusters in India and Ghana to translate the region’s techniques into “essential” everyday goods (for a Western consumer), such as towels and underwear sets. Organic cotton is sourced from fairtrade farmer cooperatives, and a fair-trade manufacturing factory in southern India make the pieces. On show was a handwoven striped bath sheet in collaboration with The Future Kept using organic indigenous (variety) undyed cotton with an iron-dyed stripe. Simple and chunky, it looked tactile (remember, we weren’t allowed to touch). The indigo spot underwear set was delightful; Made in India, they were then dyed by the Daboya community in northern Ghana.

Ashna Patel.

The printed khadi cotton vest from Ashna Patel was part of a limited collected developed as part of her Master’s project Conscious Collaborative Clothing: A Case Study on Regenerating Relationships within the Value Chain. Carried out in collaboration with Khadi London and community members in Kolding, Denmark (presumably she studied at the wonderful design school there that I’ve also had the privilege of studying at), the exploration sought to address disassociation with ecosystems that fashion and textile industries bring about. I wonder if the vest has been handled loads because the indigo is very patchy and more teal than what we anticipate indigo to look like; the patina and print give the vest a real air of ancestry.

Mishika Crafts.

Based in Jaipur, Rajasthan, this family run business champions self-reliance and economic development through their various work with artisans. They seem to be fairly new, exploring the use of natural materials and processes to create clothing. Exhibited was a khadi cotton dress, though folded up so you couldn’t really get a full idea. There wasn’t anything explaining the handmade book that was presented with it, but I liked drawings of seeds.

Images: 1-2. PICO indigo underwear set on top of a handwoven bath sheet, with photos of artisans in India and Ghana making the products; 3-5. Ashna Patel’s printed and indigo-dyed khadi cotton vest with journal publication of her MA thesis ‘Conscious Collaborative Clothing: A Case Study on Regenerating Relationships within the Value Chain’; 6. Mishika Crafts brown khadi cotton dress with handmade paper book depicting drawings of seeds.

Udyog Bharti.

The scrap indigo patchwork panel was designed by Kevin Patel and created by the artisans on Udyog Bharti, an organisation that gives self-respecting employment to “needy people” through the use of khadi and gramodyog village industries. Approximately 2000 families are earning with the help of this organisation. The use of khadi scraps in a new initiative.

Cotton exhibit.

The fabric on a plinth — undyed selvedge denim and an indigo selvedge denim — plus a skein of yarn, didn’t have any information attached to it. It does in fact look to me to be that sold by Moral Fibre, an enterprise distributing woven textiles from artisans across India, specifically those made by women (recognised because I’ve previously sold these fabrics). But perhaps it’s quite a standard cloth actually, and it’s from somewhere else (nevertheless, I love this material).

There was also a selection of cotton processing tools, from the seeds inside husks, the ginned seeds, the ginned cotton, the combed cotton roving and the charkha for spinning, along with finished dyed and spun cotton yarns.

Allan Brown.

Allan’s film The Nettle Dress premiered at the last festival in 2022 and has since toured around the UK. It highlighted his practice as an artist and someone dealing with grief. Across seven years, Allan foraged local nettles and grew flax in his allotment, both to process and spin in order to weave cloth that would then be made into a dress. An absolute labour of love.

Images: 1. Udyog Bharti scrap indigo khadi patchwork wall panel; 2. Cotton selvedge denim fabric in undyed and indigo, with a skein of indigo cotton yarn; 3. Selection of objects to highlight cotton processing, including seeds, ginned cotton, cotton roving and charkha for spinning. Also in view is Kitty Carlton-Smith’s indigo yoga mat. 4. Undyed and dyed cotton yarns ; 5. Allan Browns’ nettle dress.

Sreya Samanta + Sabrangi.

Sreya Samanta reinterprets the craft of Kantha embroidery popular in Bengal with atypical compositions and quirky motifs. The Virja saree, made from a fine count khadi cotton, is inspired by traditional windows of old South Indian bungalows that opened out onto banana trees.

Sabrangi is an organisation that teaches and trains rural women to upskill them in indigenous craft techniques in order to make fabric, sarees, stoles and accessories. The saree and stole exhibited display a ‘handbuta’ motif, which seems to be the simple lines embroidery that is then used to create other shapes such as diamonds.

Asha Buch.

The green/cream khadi cotton and eri silk saree were passed down through Asha’s family, serving as a tangible connection to the Gandhian values instilled in her upbringing. Shown with this is a book on the history and subversion of khadi — ‘Khadi: Gandhi’s Mega Symbol of Subversion by Peter Gonsalves. The charkha otherwise shown will also be Asha’s; at the 2022 festival, I had a go at spinning cotton on a charkha, this straightforward piece of equipment that requires the utmost patience and respect (I needed more time to get the hang of it, so maybe I should’ve tried again this year).

Beejkatha.

Designed and created by a tribal community in the Maharashtra region of India, the block printed quilt represents the possibilities of one single village industry. Through extensive travels via support of the Paani Foundation, Amit and Swapnaja Dalvi learnt about practical water and soil conservation techniques, and took those efforts into Beejkatha. They now work with the Kakaddara village inhabited by the tribal Kolam community.

Darcy Yearwood x Udyog Bharti.

Motivated by a personal connection to the India-Pakistan partition through a grandfather, textile student Darcy explored painting, weaving and embroidery with the aid of artisans at Udyog Bharti. The result were contemporary samples in muted earthy tones that could easily sit in many interiors.

Images: 1. Yellow saree (middle) by Sreya Samanta + embroidered purple saree and cream shawl by Sabrangi; 2. Khadi cotton and eri silk saree courtesy of Asha Buch with book about khadi’s legacy; 3. Books: Gandhi’s autobiography, Gandhi’s essay on Towards New Education, A Frayed History and Small Is Beautiful from Schumacher; 4. Beejkatha block print and quilted panel; 5. Darcy Yearwood and Udyog Bharti’s textile collaboration (with Madan Meena’s framed screenprint in the background).

Madan Meena.

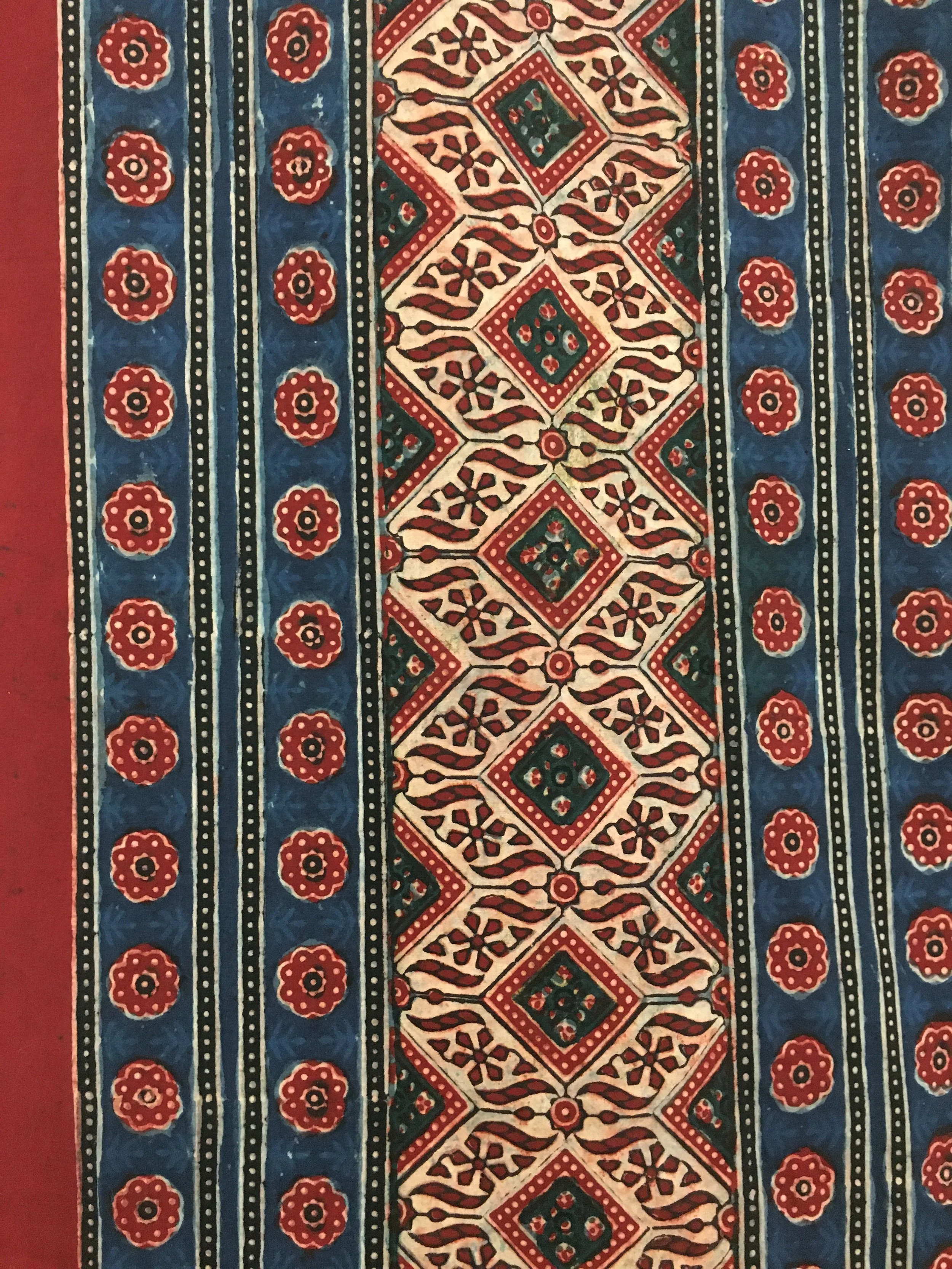

A huge printed piece of cambric fabric hangs on the wall, visible and taking up your whole perspective, as you walk into the main exhibition space. This double-sided, double-dyed ‘meenakari’ Ajrakh was created by master block printer Ranamal Khatri from Barmer in the Rajasthan desert, seemingly in response to a silk-screen design from Madan Meena following on from his research into Ajrakh (the information plaques didn’t particularly describe well in this section what went with what). Dr. Meena’s research focusses on his ancestral Meena tribe to preserve their identity.

A silk-screen print in a frame accompanied this, and showed the popular Ajrakh design ‘Ishk Pech’ in the lower half (what the massive block print looks like) with a map of journeys in the top half showing where Dr. Meena researched.

Pallavi Verma + Katy De Beer x Mishika Crafts.

Dabu printing is an age-old craft of mud resist block printing practised in Rajasthan, using locally sourced dyes and pastes, and for this collaboration between Chelsea textile students and Mishika Crafts, some fabric was printed in a motif fusing their diverse perspectives of English and Hindi. It’s probably the more swirly and subtle resist print with indigo I’ve seen (usually they’re graphic and blocky, but perhaps that’s because they’ve been designed specifically for Western audiences).

Morgan Amber.

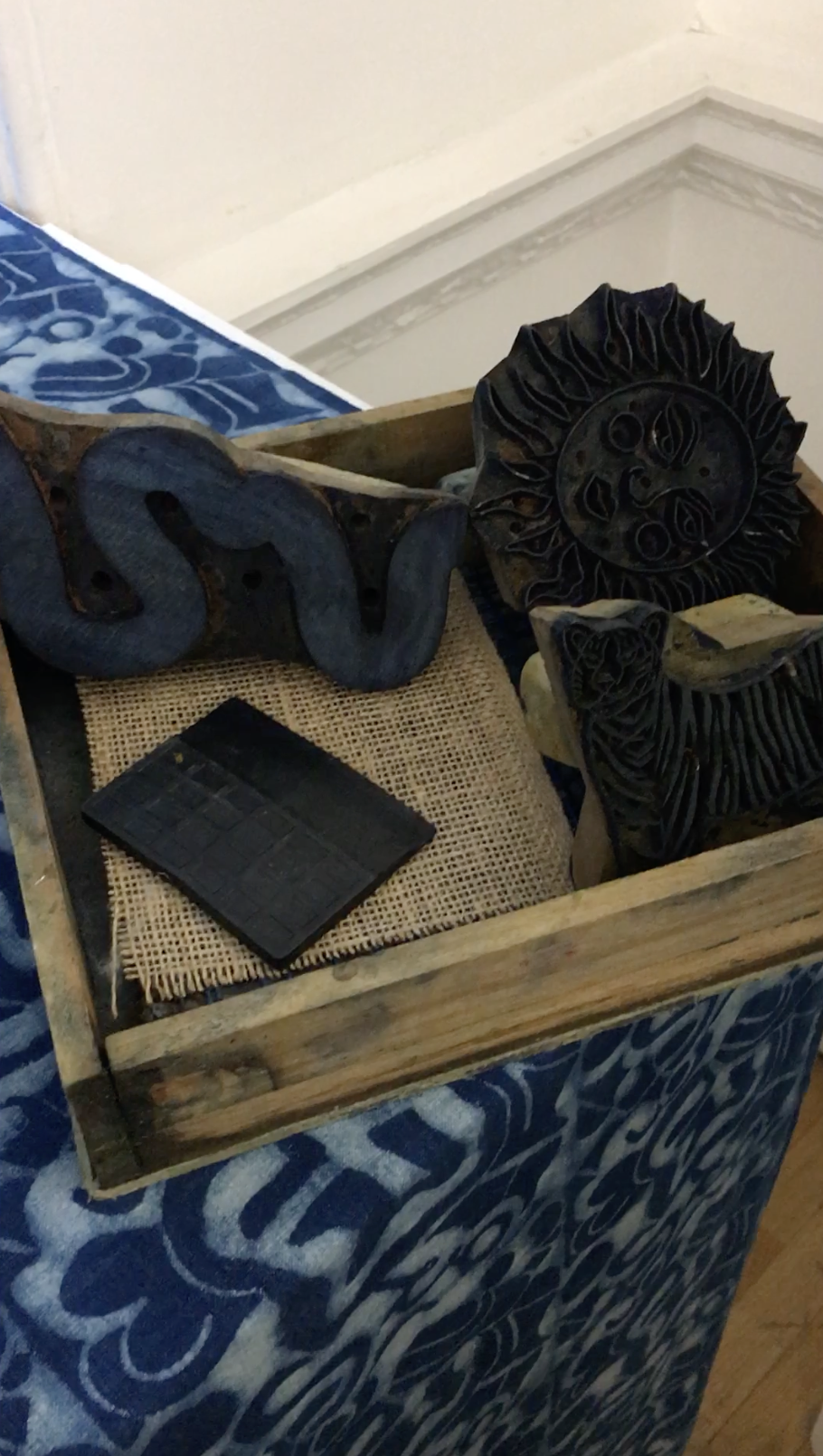

Morgan Amber was present at the 2022 festival leading printing workshops. There was this wonderful huge sun-with-face wooden block that reminded me of a duvet I had as a kid. The motifs she uses are vibrant, such as the ones in this quilt of a Bengal tiger, sunflower, sunbird and little hearts, so merging identities. The candy-striped binding is also fun. Morgan now partners with Mishika crafts.

Images: 1-2. Madan Meena x Ranamal Khatri block printed handwoven cambric fabric; 3. Madan Meena framed silkscreen of the Ajrakh design and intricately carved woodblocks used in the printing; 4. Pallavi Verma + Katy De Beer x Mishika Crafts mud resist and indigo-dyed fabrics; 5. Morgan Amber Vasanta quilt with cushions; 6. Morgan Amber carved wood blocks sat on a piece of Pallavi Verma + Katy De Beer x Mishika Crafts fabric.

Miyar Mufflers.

A super niche product line designed by Rahul Noble Singh and created by the craftswomen of the Miyar valley of Himachal Pradesh, these mufflers and bed throws use handspun and hand-knitted own-sheep wool. With a childhood spent between Scotland and the Western Himalayas (both often rurally cut off for certain seasons), Rahul wanted to establish community entrepreneurism amongst local women.

There was an unusual adornment of seeds; the seeds of the oroxylum tree are brought in their large pods from a holy lake to Himalayan Buddhists, then caps or vessels are decorated for when serving a welcome to visitors. To me this was a thoughtful addition that made the item more than simply a hand-knitted ‘thing’ from tactile wool.

Sarah Jerath.

Sarah Jerath exhibited at the 2022 festival with a rail of garments elegantly hand-stitched from cotton and wool. They looked and felt comfy, so was pleased to see this indigo dress and undyed quilt for 2023, again appearing familiar and cosy. Originally a ceramicist, the fragility there is translated into textiles with intricate yet functional stitching. The cotton comes from the Beejkatha regenerative cotton-to-cloth value chain.

Kullvi Whims.

A social enterprise based in Naggar, Himachal Pradesh working with artisans of the Kullu valley, Kullvi Whims sources wool exclusively from nomadic shepherds who traverse the Himalayan ranges. I don’t mean to make this comment solely from their products and it’s not even directed from what they produce in particular, but there are a lot of these ‘simple’ items (as seen with Miyar Mufflers above) that make their way over into Western homes by marketing them as ‘eco’. I feel that there are limited sales opportunities for such beautiful stories of regeneration, and all we can do over here is hope someone is in the mood to gift (because these are gifty items). The product and a sort of economy has been established, so how can we support it — especially if we don’t want to buy more stuff of things like scarves that we don’t need?

Amir + Anju Singh.

These are a couple based in a remote village in the Lahaul valley of Himachal Pradesh who are guardians of 30 sheep. Often the winter seasons are harsh, so they spend time processing the fleece from fibre into fabric, a total expression of living in great connection with land and seasonality; that slowing down over colder months to sustain oneself. The fabric (and wool rovings?) exhibited was acquired by Ashna Patel on a research trip exploring scales of decentralised textile production across India. I love hefty cloth like this, and the fact it was produced by two people is amazing.

Images: 1-2. Miyar Mufflers example of bed throw and muffler, with oroxylum seeds on a pom pom chain as an adornment; 3. Sarah Jerath quilt and dress; 4-5. Kullvi Whims shawls, wool yarn skein and photographs of artisans; 6. Amir and Anju Singh’s decentralised hand-processed and woven diamond weave cloth, with balls of wool roving.

Raddis.

Raddis® is transforming the cotton value chain with a transparent “farm-to-product” system creating fibre, yarn and finished garments. Initially an arm of Grameenas Vikas Kendram, a society that facilitates and creates sustainable agricultural business and marketing models, Raddis has been standing apart and providing opportunities for change that has proven clients. They exhibited t-shirts made of rain-fed Raddis system cotton grown in South East India, along with examples printed for the Dutch Tomorrowland music festival that were to be sent back and recycled for future festival t-shirts. A paper passport accompanied the garment, with QR code so the owner could trace the garment’s journey. This is just one of the longstanding partnerships and commitments they have made with clients, so establishing them as a place to go for regenerative cotton solutions.

Where Does It Come From?

Jo Salter founded this brand to show how apparel transparency could work, and in the respect of explaining where the item comes from, that works. However, as someone who previously worked for an atelier that was transparent in everything (labour time and costs, transportation time and costs, material costs), I get fed up of brands claiming transparency when there’s simply more that can be done. Perhaps that’s just not the point here; as I’ve said, it explains where the product comes from (the fibre, the processing, any printing, the manufacture). I also personally wish it wasn’t this ‘ethical’ aesthetic, but I’m obviously not their customer. My point is that the brands I do like could also do similar (though it’s not easy or quick).

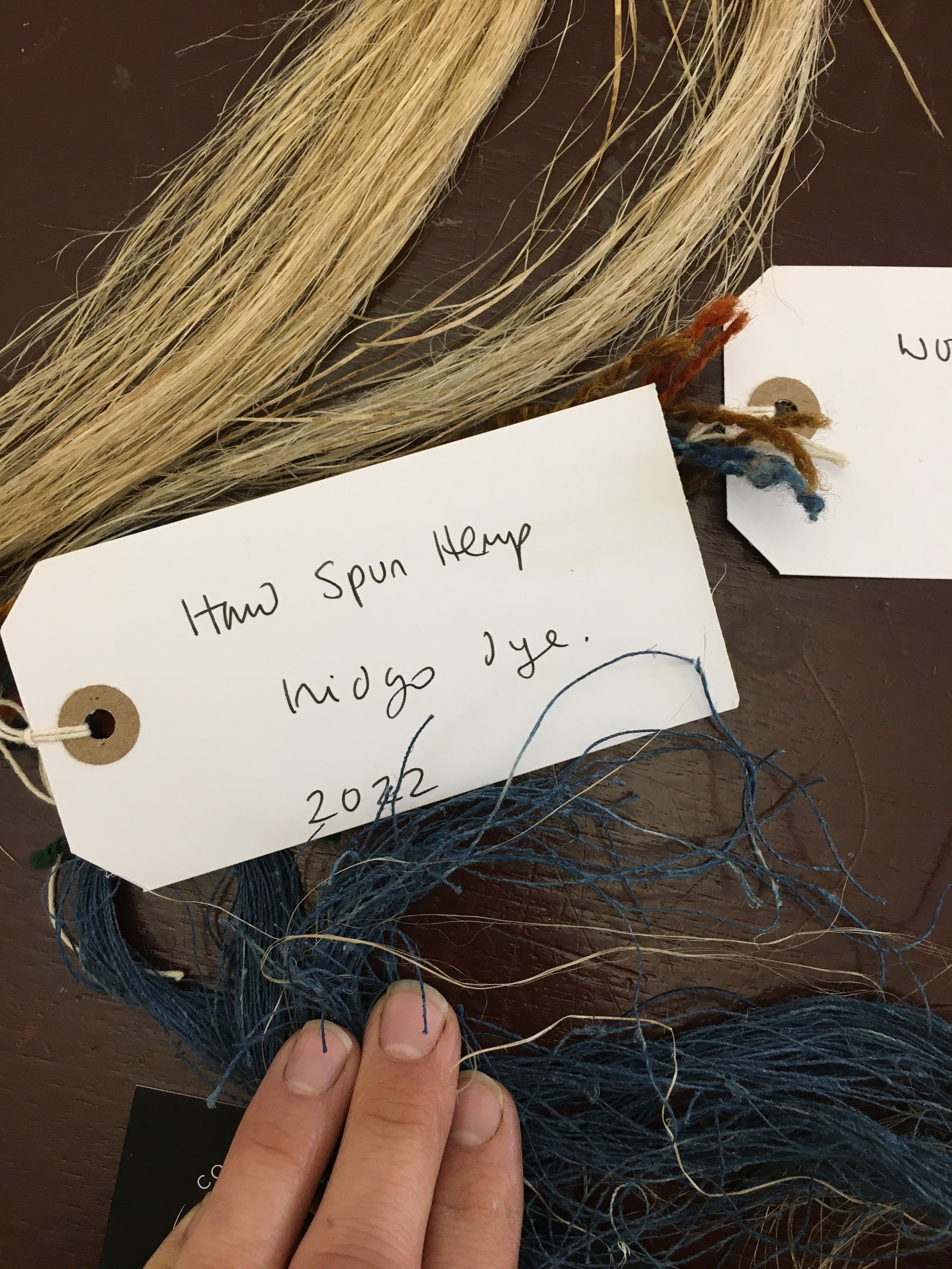

Contemporary Hempery.

A fairly newly established hemp farm with in-house processing and weaving, working to establish an understanding of how hemp infrastructure and awareness needs to improve in the UK (or first, England). They’re now at a point where they have various samples from the last two years’ harvests. Shown were the heckled fibres of hemp after either water or dew retting (or unretted, along with samples of a light and a chunky wool-hemp blend, and some indigo-dyed handspun yarn. These I did touch, as I feel it’s simply rude not to.

Images: 1-2. Raddis®Cotton t-shirt and product passport; 3. Where Does It Come From? printed scarf from Moralfibre fabrics; 4-6. Samples of retted and processed hemp yarn, and samples of woven wool-hemp from Contemporary Hempery.

Threads of Change as a standalone exhibit featured ways that designers may collaborate with artisanal communities, some of the fibres they could use, and in what potential ways they could be regenerative (socially, economically and environmentally).

Some of the challenges I feel the exhibition highlights are:

India-focussed ⇾

Primary inspiration came from India, which was expected considering the exhibition venue, so if that particular aesthetic or community is not for you (because you have other values or styles), then are the solutions translatable? Ok, so India is actually very diverse, with each region (each village in fact) having particular skills and techniques that they use for their craft, but it is a distinct identity (which is perhaps why the Chelsea students have tried to Anglicise it… and why we find graphic-looking prints).

Time for research? ⇾

On top of this, it assumes you’ve either got time to go on a research trip or time to put in funding bids, which I surmise is a huge barrier for designers simply wanting to incorporate a regenerative element into their brand or work. It anticipates that you will take this on as a lifetime project, and that’s just not where designers’ heads are at currently, because our fashion system doesn’t allow room for this thinking.

It suggests that if designers are to work regeneratively with artisans, then they need to do so independently or with organisations — and perhaps this is the best course of action regarding respect for culture and language. But again, siloed designers (or restricted designers as part of brands) mean there is little room for commitment of this type. So what smaller actions can designers take? Is it a small step such as PICO make with their starting point of an underwear set before moving onto a towel?

No leather. ⇾

Leather is missing again in the ‘regenerative fashion’ conversation. I feel it remiss not to attempt to include more fibre options, and though leather is often taken as a skin (so not a fibre) its structure is that of fibre, so that can’t be the reason it’s missed (out of Safia Minney’s Regenerative Fashion book too). Even if the exhibit here is solely focussed on India, well, India produce 13% of the world’s hides and skins (of cattle, buffalo and goat), and are the fifth-largest exporter of leather footwear and clothing according to the India Times. There is a huge opportunity here to shift the system for more regenerative economies, environments and societies by looking to leather.

Minimal bast fibres. ⇾

Again, because the focus was on India, there are minimal projects using bast fibres, such as flax, nettle and hemp. Wool and cotton are key, despite the fact that Himalyan tribal communities process hemp and nettle for the most outstanding cloth. Diversity is missing; visitors seeing these projects would be undeniably wowed and inspired, but it isn’t truly indicative of the scope of opportunities.

Summary. ⇾

In summary, I’d like to visit an exhibition that does curate the resilience offered when regenerating the markets of natural fibres. This is so that visitors have chance to witness how it could work for them and their vision, their values, their aesthetic. Unfortunately, 15 years on from when “sustainable fashion” first really started being bandied about, I still feel that we’re not contemporising enough; there’s a distinct look about “ethical” products. Maybe it’s more of a visual merchandising thing, where it all simply needs to be styled in a way that captures the masses. That comment alone I’m sure would get grumbles — that it shouldn’t be for the masses because they drive scale and speed and growth (is it them that drive it?)

Yet, it’s true that a luxury or a mid-range brand implementing regenerative strategies for their products will look and feel different to an independent maker bringing forth these community stories. And it’s the need for standardisation that sets luxury/mid-range brands into creating contemporary products with a hint of the new regenerative strategy, while indies can go all in. Which is better? Should one be better? Can we showcase all of these solutions side by side: the ones that are Responsible Wool Certified against the ones that are using traceable wool from a farm down the road? Each shifts the system in their own way, and both are moving forward. I won’t speak of greenwashing or miscommunication, and of course I’ve not mentioned costing.

Though I really do feel that the diversity of solutions has not yet been established in one fell swoop so that we can all objectively make decisions on what works for our particular product/business.

Nevertheless, it was a lovely, well-curated exhibition that was displayed as best as it could be (I’ve mentioned some confusing info plaques already, but maybe it was just I confused, and I really wanted to touch everything depsite ‘please don’t touch the exhibit’ signs everywhere). I discovered new makers, designers, projects, businesses and organisations. I learnt about some traditional techniques.