Plastic free periods.

Plastic free periods, and how to embrace menstrual equity.

Understanding the social context of the taboos involved with menstruation can help us establish why period products are a leading cause of plastic pollution in our waterways, and why there is still an access issue in terms of education of cycles and of obtaining hygienic products, both necessary for the safety of people who menstruate.

I started my period during a science class in year 8. I think I was aged 12. I remember feeling something unusual coming and asking to go to the bathroom, I guess putting some toilet tissue in my knickers to stifle the flow until I got home that afternoon. I imagine I was aware it may happen soon, as I'd already developed boobs and had pubic hair. I'm unsure what the discussion was at home, though think it was simply going to the shop for some pads (mum was an Always fan). I suffered from dysmenorrhoea, often being on the verge of blacking out and needing to lie down on a cool floor (usually a bathroom if I could find one, sometimes pavements) until I started shivering and the episode passed. My flow wasn't even particularly heavy, but it was the understanding that I'd be totally fatigued that gave me an excuse to skip PE lessons. I also suffered greatly from iron and B12 deficiency, not helped by being both vegetarian and a menstruating female.

I don't recall our school education as being particularly involved in regards to menstruation, and neither at home where I don't think I had many chats. At about aged 15, a doctor suggested I go on the pill to help with the cramping, but I didn't trust that I wouldn't get messed up by hormone shifts - somehow at that age cognisant of unintended consequences, which fortunately helped me in adult life when it became more apparent at how tricksy the pill was.

When I think back to how I acted in regards to my period, other than the above, I was very aware at how I had a particular smell during my period and that would feel embarassing. I'd stuff pads into my skirt or jumper sleeves so I had them handy during the day, rather than heading back to our lockers, but I have the vague recollection of boys finding it funny nicking these things. The intricacies though of how I was affected by my cycle in terms of energy levels was only in terms of when a fainting episode may occur (throughout the 7 days that I was bleeding), and not the other two or so weeks when there were no visible associations to menstruation.

These intricacies I am still, at aged 35, trying to get my head around. A noticeboard with the possible symptoms and phases sits on my desk, while my seasonal work plan highlights what phase I will be in when, and how this sits with the lunar phases. It's a heightened awareness that I've worked at, but there are so many external factors at play that it can be difficult to establish what symptoms are menstrual and what aren't. And this is why, 7 years on, I'm still battling with my GP about an ovulation-related electric shooting pain in my groin.

And this management of menstrual symptoms is one of the challenges in (heavily male-led) work environments where it makes those on their period seem weaker. And if you're not in flow at that time, then there is no tangible evidence of your pain, so it’s like (and from a personal standing too) please just shut up and get back on with your work. There's also then sports environments to consider. Plus, cultural differences affect the roles that women have at certain parts of their cycle.

So with that story in mind, here are some considerations for better understanding periods, and how we can shift to plastic free products to help solve some massive issues. There are some resources for each to continue your learning and curiosity.

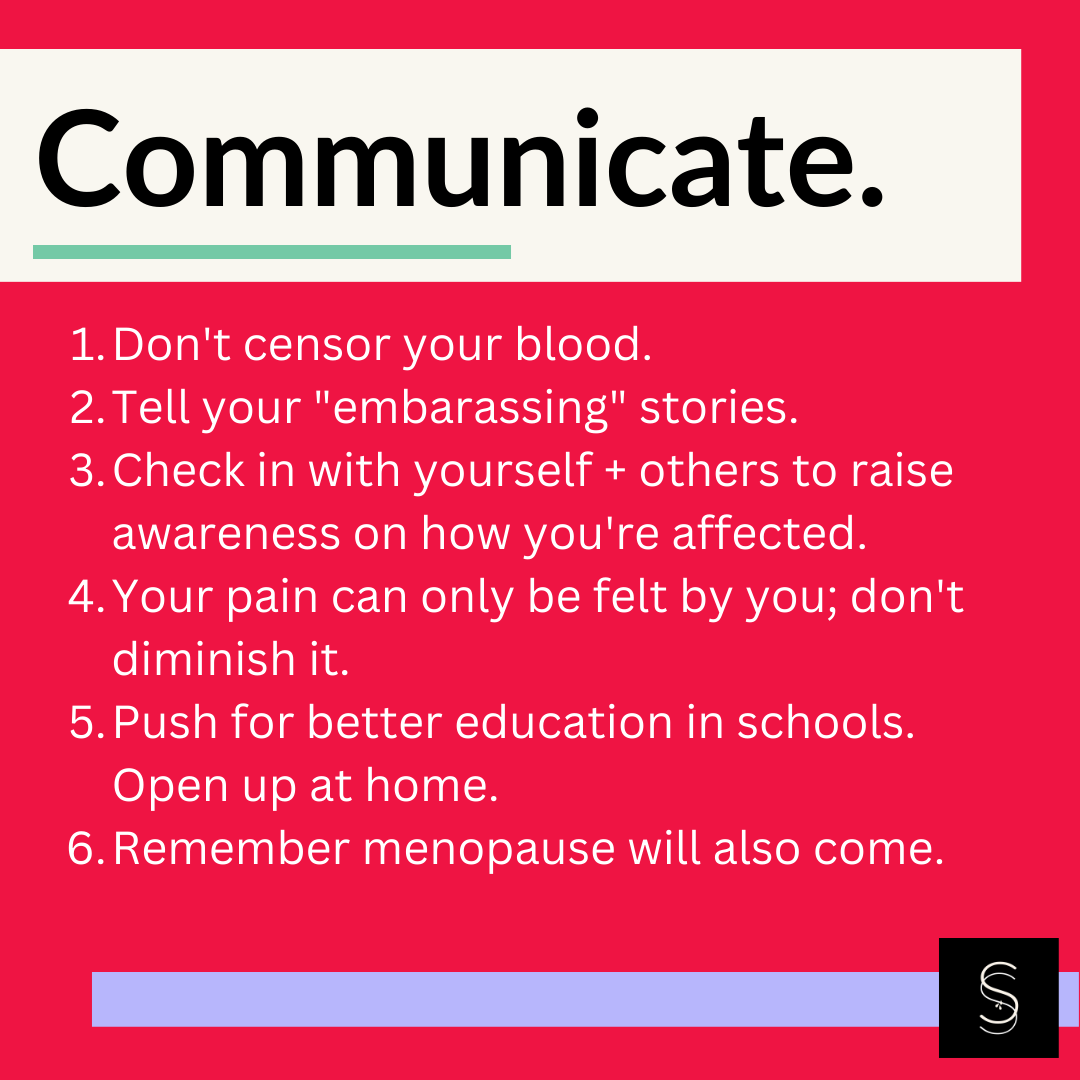

Images: 1-5. Graphic assets showing actions you can take to go plastic free, communicate more and better on menstruation, how you can become more attuned to your cycles, and some suggestions on how to campaign for legislative change.

Environmental.

On average 11,000 menstrual items are used in a lifetime.

Up to 2 billion period products are flushed down the toilet in the UK each year, blocking our sewers and creating overflow that escapes into our rivers and seas [City to Sea].

Flushing behaviour has led to period products now being the fifth most common item found on European beaches – more widespread than single-use coffee cups, cutlery or straws (from the EC Reducing Marine Litter: action on single use plastics and fishing gear report).

A big-brand pack of 14 period pads contains the same amount of plastic as 5 carrier bags - on average, there are 36g of plastic in every packet of period pads. That’s 2.4g of plastic per pad, and 2.5g for the outer pack itself. You wouldn’t flush plastic bags down the toilet, so why are we flushing 1-2 billion period products every year in the UK? [City to Sea]

I had to call out Fluus when an ad of their's came up on my Instagram feed, saying that they'd invented flushable pads. Out of about 15 responses from friends about how ridiculous this statement was, I had one person saying "what's the issue, they're biodegradable?"

Why do you need to flush pads and still potentially block your drainage system ("around 80% of sewer flooding is due to blockages in wastewater networks, costing the industry around £88 million alone just to manage blockages" [EPA]?! Fluus' argument is that they're saving the waste from landfill, but simply avoid single use and you won't even need to consider landfill. They're also £5 per 15 (33p each), while Bodyform and Always are from 7-22p each. This isn't exactly inviting people in to a fight against period poverty. (Yoni, an organic cotton disposable pad is 35p each at Sainsbury's, and similarly organic cotton/wood pulp Natracare on Ocado are 19-22p each, but in comparison these use one-to-two named materials while Fluus have patented their "tech" and are not fully disclosing materials i.e. "biodegradable polymers" and "cellulose plant fibres").

If just 20% of people in the EU used a menstrual cup instead of single-use items, it would prevent 100 tonnes of waste across the 27 EU member states, every year. [City to Sea]

And if you care about carbon footprints too, well "by switching from tampons to menstrual cups people can have 16 times less carbon impact, saving 7 kg CO2e over a year" [Zero Waste Scotland]

The above focusses on pads, but other disposable products include plastic applicators, tampons and the wrappers themselves.

The majority of high street branded tampons are made with rayon, a semi-synthetic material that undergoes a myriad of chemical processes (some brands state it as wood pulp, which is technically correct, but this belies the chemical nature of transforming it into rayon - otherwise known as viscose). These you're inserting inside yourself. Even if you find one that does say it's made with cotton, they will have been bleached, or will have added synthetic fragrance. So organic unbleached tampons, and preferably those not wrapped in plastic, are the safest (though you still have Toxic Shock Syndrome to contend with).

Menstrual cups, though feeling like plastic due to their malleability, are actually made of medical grade silicon, latex or a thermoplastic elastomer (TPE). These have been developed to be safely inserted inside, and can be easily cleaned particularly in boiling water to sterilise them.

Reusable pads and pants require a larger investment because you're essentially buying an accessory made from the materials you'd expect of your normal clothes. They have all been researched and developed for all types of flows and all sizes of people, so you're also in a way paying for this shift. I use Dame's reusable pads; 3 years ago when I had my copper IUD removed, my period shifted from 7 days to 2 days (which the doctor remarked was good, not weird), and so I can get away with usually 3 pads. I use organic tampons for days I'm doing sports. I haven't tried any pants because I'm quite specific on the shape I like, but one day maybe I'll make my own (as patterns exist). I do have a menstrual cup - it’s probably 8 years old - but after many failed attempts to get it to be comfortable, I gave up; the market has many more options now, with some also offering a satisfaction guarantee if you happen to select the wrong size, but the reusable pads and organic cotton tampons work for me. You could also have a go at making your own reusable pad with Plastic Free Hackney's pattern and instructions (created by WEN).

Take action:

Here's a resource from City to Sea on the options for all the menstrual products with a resource specifically for those with additional needs.

Here's another resource from City to Sea that highlights where you can find retailers that sell menstrual products. It's unclear when it was produced, so the likes of Asda do indeed now stock a plastic free alternative (&Sisters organic unbleached tampons).

Sign up to the Women's Environmental Network's mailing list for discount codes on menstrual products.

Read the Seeing Red: menstruation and the environment report from WEN.

Learn how to insert a menstrual cup through the informative video from AllMatters, along with a blog on how to care for your menstrual cup.

Download the digital Positive Periods Guide from Juno, including stories on approaching puberty and your first period.

Listen to the 28ish Days Later podcast from BBC Radio 4.

Images: 1. Sanitary pad on the beach, bloated with water and sand; 2. Me holding my baggie of reusable pads from Dame; 3. My reusable period pads and storage bag from Dame; 4. Emptying a menstrual cup [credit: AllMatters].

Period poverty.

Period poverty is a global issue affecting those who don’t have access to safe, hygienic menstrual products, facilities and education. Those who experience period poverty are unable to purchase the menstrual products they need and in many cases, it causes them to be unable to participate in daily life. [YouGov]

With the cost of living crisis, hits on supply chains, wars, and an increase in amount and intensity of natural disasters, access to period products is worsening - "each period can cost on average £10, that’s £130 a year and £4940 over a lifetime" [Bloody Good Period]. On top of this, period products are taxed even though they’re a basic necessity rather than a luxury. Fortunately the UK tax was lifted, but not on reusable period pants, so continuing the lack of accessibility for safer and more comfortable options (the pants are particularly great for school years). And as of January 2023, retailers who have “removed the tax” have retained the same product price.

This is alongside already existing challenges in talking openly about menstruation due to stigmas attached (for example, that those who menstruate are dirty and should hide). "In lieu of sanitary products, many people are forced to use items like rags, paper towels, toilet paper, or cardboard. Others ration sanitary products by using them for extended amounts of time. [Ashley Rapp and Sidonie Kilpatrick]

Research by Plan UK found the number of young people struggling to access and afford period products in the UK increased from 10% to 30% during lockdown.

Period poverty encompasses not only this lack of access to products, but also inadequate access to toilets, hand washing receptacles, and hygienic waste management. If we look back to the above segment on environmental factors, flushing of period products is a huge habit, and could be because there is a lack of suitable facilities in bathrooms (including those that trans, disabled and homeless folk would need to access).

Homeless people and refugees who menstruate may struggle to access these basic needs, which makes it incredibly difficult to safely care for themselves whilst menstruating. People living below the poverty line (9.2 million people in the UK) may struggle to afford sufficient water bills for hand washing or washing/sterilising reusable products.

Take action:

Natracare's Shade of Red zine about the gender identities of those who have periods.

Watch 'Period. End of sentence' on Netflix [26 minutes, 2018].

Read about Bushra Manhoor's grassroots movement - Mahwari Justice - providing menstrual aid to those affected by the Pakistan floods of 2022.

Sign the petition to urge the UK goverment to fully follow Scotland's lead in providing free access to period products for England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Join in with the Rethink Periods campaign to provide free unbiased education and products to schools.

Organise a fundraiser to support Bloody Good Period with their mission to provide free period products.

Read why menstruation is a human rights issue [Scheaffer Okore for WEN].

Learn about the period tax, and in particular check out the Period Tax Map where you can see the amount of countries still charging VAT on these products.

Images: 1. Campaign poster from Bloody Good Period; 2. Recipients of period products from AllMatters; 3. Campaign to abolish tax on all period products in the UK, including reusable period pants; 4. Zine excerpt from the Juno Positive Periods Guide.

Health.

As above, both physical and mental health can be affected when there is no adequate access to hygienic sanitary products or services, including safe spaces to change and clean water to wash.

Alongside this, the materials themselves (as mentioned under the 'environmental' heading) affect internal health through the use of synthetic ingredients and by contaminated wastewater when products are dumped.

Period products have been found to be a considerable source of exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) such as phthalates, bisphenols and parabens for women. These chemicals are linked to cancer, reproductive and developmental disorders, birth defects, asthma and allergies. This is because the skin of the vagina is extremely absorbent, so the absorption rates are higher [study from Chong-Jing Gao et al via WEN].

"Synthetic fragrances including those added to period products can contain a cocktail of up to 3,000 chemicals [Chem Fatale report, 2013]. Lack of specific legislation and transparency [WEN] about the hidden ingredients in our period products means we could be exposed to harmful chemicals and fragrances without our knowledge. Chemical fragrances can interfere with the pH balance in the vagina, as well as the balance between good and bad bacteria [Zero Waste Europe] which help the vagina to stay clean. This can lead to irritation and infection [Very Well Health], which in turn may produce more odour. Often the ‘smell’ we associate with periods is actually due to the mixture of oxidised blood (blood out of the body) mixing with these perfumes - that incidentally are not named due to intellectual property.

If we look at the materials that our usual internal menstrual products are made of - the pads and the tampons - we tend to think they're cotton. This is the beauty of rayon; it can be created to resemble cotton fabrics, but at a cheaper cost. It's cheaper because it uses wood pulp (from deforested trees) rather than cotton (as it takes up less land), and undergoes a semi-synthetic process using solvents to break the fibre down into a usable fibre. It also needs to be bleached with chlorine to transform it from a brown fibre to a white fibre.

We believe that cotton is safe and clean, but as shown in the above statistics, even if your product is cotton (not rayon) it will still be doused in processing chemicals and fragrances that are not natural. Cotton itself has its own issues, from modern day slavery, to extensive pesticide use, to farmer suicide from incurring debt to conglomerates like Monsanto for GM crops. Choosing a brand that uses certified organic cotton is helping to shift the system, while ensuring you're not putting anything too dirty inside yourself, but still a word of caution needs to be mentioned that all fibres and materials undergo processing of some sort.

And though there has been a shift in availability on the market of healthier products, with at least 13 plastic-free options added to market since 2019 [City to Sea] there are still taboos about periods being smelly. Some manufacturers are playing the old game of adding stuff that isn't needed, such as antimicrobials and antibacterials (the vagina cleans itself).

One such example is nanosilver – which is basically very, very tiny particles of silver – these tiny particles can pass through the skin, accumulate in our body causing unknown health impacts while also causing allergic reactions [Blinova et al].

Additionally to health, there is the impact emotionally and mentally. From fighting fatigue in a traditional office environment, taking days off school due to embarassment or cramping, to general lack of concentration or overwhelming emotions including irritability and upset. Symptoms and effects are different to each person, which is why it can be tricky to analyse what is menstrual related - and why I above mentioned that I'm still trying to figure this out myself at aged 35. It also fluctuates according to your age and to stressors; it was confusing when my flow shifted, and to hear from my doctor that it was good rather than unusual didn't help my concerns.

Take action:

A letter template to supermarkets asking them what they're doing to address the plastic in the products they retail.

Sign WEN's open letter or email your MP explaining why transparency of period products is essential.

Read the Toxic Free Periods report from WECF International.

Find more statistics in the Environmenstrual Factsheet from WEN.

Record your menstrual symptoms to address your cycles more deeply [City to Sea's is basic but a useful starting point].

Watch the webinar This Could Turn Toxic between Plastic Free Periods, City to Sea and Natracare on endocrine disruptors.

See a timeline for chemical testing of period products [Women's Voices for the Earth].

Read about chhaupadi and menstrual taboos from charity Action Aid.

Listen to the Period of the Period podcast from Kelly McNulty.

Listen to the Female Athlete Podcast (suitable for anyone).

Images: 1. Ad from Dame similar to one that was originally censored due to the tampon string hanging out; 2. Screenshot of the first episode of the Female Athlete Podcast that talks about a ‘normal’ menstrual cycle; 3. Partial screenshot of the Women’s Voices timeline of chemical testing on period products mentioned above; 4. The contents of a hygiene kit that ActionAid distributed to refugees in Greece [Credit: Karin Schermbrucker/ActionAid].

This isn't an extensive article - I've barely touched on the menopause - but enough to whet your appetite for the main issues within the conversation around menstruation - and the actions you can take to improve the system that demeanS and undermineS people who menstruate.

Though I don't like to use the word "empower" (as it signifies someone doesn't have power on their own), by shifting mindsets to one that agrees menstruation is not an illness, then there can be an improvement to power imbalances and equity that forces girls and women and trans folk to be lesser and weaker, simply because they were born with a cycle the other half of the population doesn't have, and one that in fact keeps our full population going.

By improving menstrual education, hygiene, health and product access then there can be improvements to other types of education, to work, to money; girls are less likely to miss school, would be better equipped to take care of themselves, and would already have opportunities afforded to them because they have dignity and are more comfortable. Join in with Bloody Good Period's Embrace Menstrual Equity campaign.