Among The Trees.

Reflection of the 2020 Hayward Gallery exhibition featuring artists that explore our relationship with trees. I visited during a pandemic lockdown lift and here I revisit.

Among the Trees was at the Hayward Gallery, London 4 March – 31 October 2020. I visited during one of the lockdown lifts, so the gallery was sparser in visitors, more controlled, everyone in masks. The subject of trees probably hit hard for those unable to access much green space over this period, and then to see them essentially devoid of life in this exhibit could’ve been an additional knock rather than something uplifting.

While there were pieces that explored the lifeforce of trees and forests, such as the digital screen of Finnish birch from Eija-Liisa Ahtila - Horizontal – Vaakasuora [2011], it was quite heavy around the industrialisation and commercialistion of trees, such as Guiseppe Penone - Tree of 12 Metres [1980-82].

Some five years on, I’m taking a look back at the photos I took to return to that moment, and share with you the artists and works.

I appreciate the description from the Rowley Gallery blog of the exhibition, which had come up in a search engine. I’d used the words and images to centre myself back in the gallery, and reminded me of all that I’d seen but not, apparently, taken photos of (or my photos got lost in the ether).

“Unlike classical representations of landscape, many of the works in this exhibition avoid the easy orientation offered by foreground, vista and horizon. Instead they invite us to get lost, and to experience – on some level – that uncanny thrill of momentarily losing our way in a forest, and seeing our surroundings with fresh eyes.” — Rowley Gallery blog, March 15th 2020.

Vastness.

Eva Jospin — Forêt Palatine [2019-20].

This carved work of cardboard enables visitors to feel among the trees. It’s a strange one, to have an exhibition of this title in a Brutalist setting, where there’s a juxtaposition of warm and cold / browns and greys. The cardboard layers somewhat soften the scene, and yet you’re able to envision the vastness of a forest. Interestingly, Jospin talks in this short video of how cardboard is normally a starting point, yet she wanted to show it in a more precious and less industrial setting — taking the material back to its own origin, and particularly one where the work evolves like a natural forest.

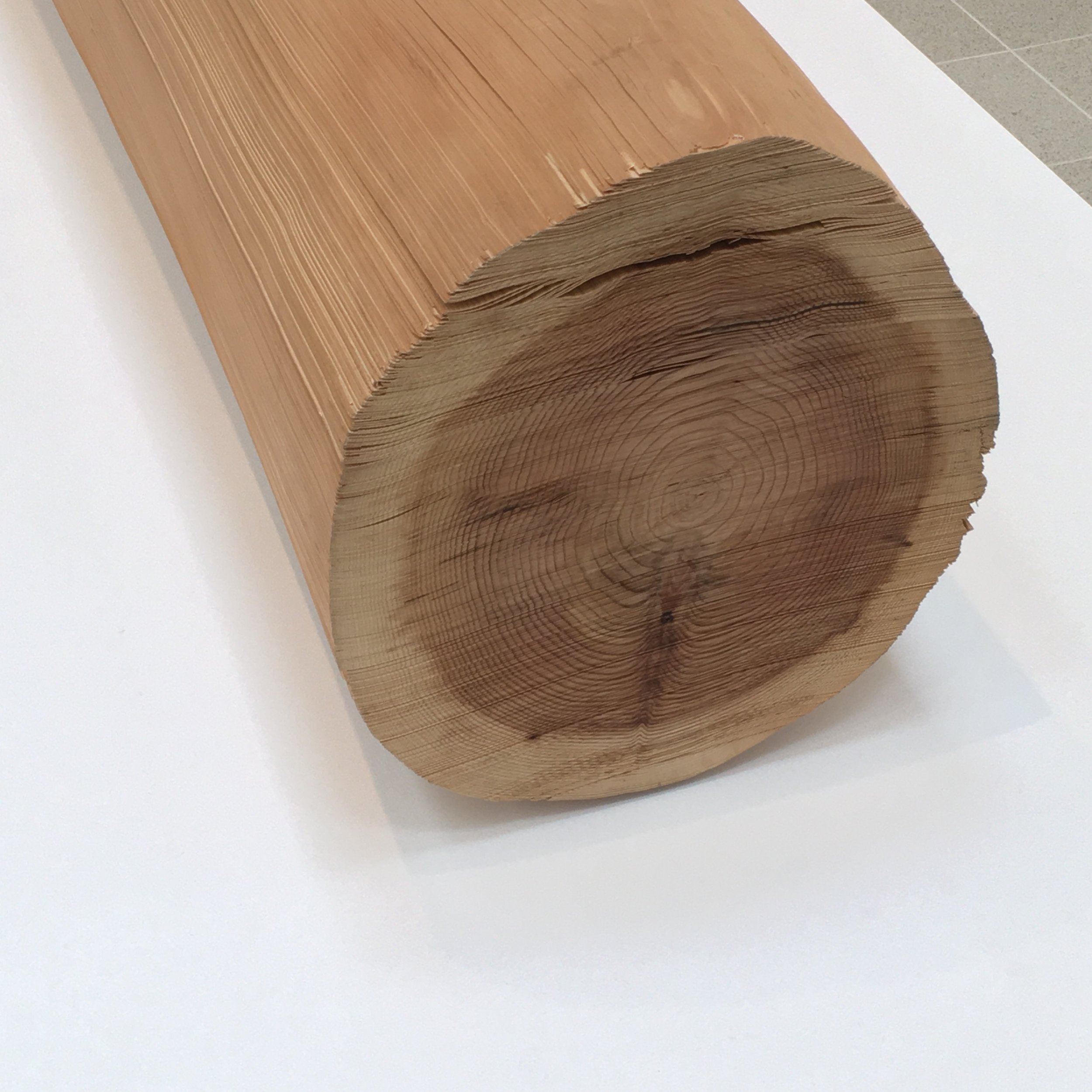

Giuseppe Penone — Tree of 12 Metres [1980-82].

This American larch timber block has been carved away following the knots, to reveal where branches would have been in the tree’s life. The tree was split in two, with the top half placed upside down. Visitors can’t quite grasp the full scale of the tree’s twelve metres, even when traversing up the gallery staircase to the top. The timber wasn’t fully carved, leaving the revealed bare trunk standing in its industrial block, somewhat motionless in time and purpose.

There’s a four-minute video from the Hayward Gallery’s Director, introducing these two works.

Images: Eva Jospin — Forêt Palatine [2019-20] / Giuseppe Penone — Tree of 12 Metres [1980-82].

Submerged.

Robert Smithson — Upside Down Tree I, II, III [1969].

This series was made on route between New York to the Yucatán Peninsula (Mexico) via Florida. Branches of young trees were removed and then replanted roots side up, challenging our “anthropomorphic tendencies” to identify with the vertical stature of trees. What isn’t clear is whether the trees were dug up and planted in situ, like here on the beach. I hope so, so at least they remained at home. I do find this work destructive, and continues the ideology that we should control nature.

Mariele Neudecker — And Then the World Changed Colour: Breathing Yellow [2019].

I remember this one feeling eerie. There was an accompanying print — Much Was Decided Before You Were Born [2001] — of a submerged forest in a green tinged liquid. You see the frame and so in a way feels abstract because of the edges. The below image though, is actually of a sculpture in a glass tank, but for some reason I wasn’t inclined to take a photo of the tank and rather just the close-up. As if I wanted to remember only that feeling of the drowned apocalpytic vision.

Images: Robert Smithson — Upside Down Tree I, II, III [1969] / Mariele Neudecker — And Then the World Changed Colour: Breathing Yellow [2019].

Solitary.

Robert Adams — Fort Collins, Colorado [1976].

I struggled to get a photo of this frame. Reflections of visitors crowded the lone tree, taking away from the solitude. That feels apt looking back, at the time period, when everyone was mistrusting of others and yet we couldn’t escape. We were alone and not alone. Adams’ series of photographs highlight the changing landscape of the American Midwest, and I guess here the single tree amongst what appears to be desert is a signifier of industrialisation and changing climate — even in the 1970s.

Myoung Ho Lee — Tree… #2 [2012].

Another example of deconstructing a tree from it’s environment is Myoung Ho Lee’s use of the canvas backdrop to separate a tree from the surroundings while retaining those surroundings. While Adams’ shot captures a solo tree, Lee’s forces the tree to be solo.

Images: Robert Adams — Fort Collins, Colorado [1976] / Myoung Ho Lee — Tree… #2 [2012].

Memory.

Roxy Paine — Desolation Row [2016].

I think I’d taken a close-up photo before I noticed on the information plaque that it requested ‘no photography’. It’s years after the fact now anyway, and don’t believe I shared it at the time. But taken like this, out of context of it being a sculpture, it could look real. A forest still in process of burning. It has been described by the artist as a cataclysmic aftermath and “stillness after the chaos and destruction” from humans controlling nature.

Giuseppe Penone — Propagazione [1995-2020] / Albero Porta [2012].

Along with Tree of 12 Metres elsewhere in the gallery, were three other works of Penone’s. The wall drawing featured a thumb print in the middle, so melding human marks with tree marks, though the rings apparently came from those of the carved out cedar as shown. This carved cedar, Albero Porta [2012], follows the same process as Tree of 12 Metres by carving where knots were visible, in order to identify where branches were before the trunk was cut. Additionally there was a sculpture of timber whips seemingly growing through bronze — Soffio di foglie [1982] — which is in fact a cast of the shape of the artist’s body made in a pile of leaves.

Images: Roxy Paine — Desolation Row [2016] / Giuseppe Penone — Propagazione [1995-2020] / Albero Porta [2012].

Pollution.

Pascale Marthine Tayou — Plastic Tree B [2020].

This one is described as “improvised beauty found in unexpected places” with the artist often mixing “beauty with ugliness” from natural and inorganic materials globally ubiquitous. It was indeed striking; a splash of colour in an exhibition obviously imbued with earth tones. And is indeed simple; it’s a wild tree strung with plastic bags. Often this is all that’s needed to make a statement and have the viewer ask questions.

Simryn Gill — Channel #1 - #9 [2014].

These nine photos are from a larger series documenting pollution caught in mangrove trees close to the town of Port Dickson, which sits on the Malaysian coast of the Straits of Malacca — the main shipping channel between the Indian and Pacific oceans. The black and white photos almost pale in comparison to the vibrancy of the gallery installation, as if the latter is more real than the documentation. They’re shot so elegantly, despite the inference of destruction. I find it interesting that a lot of landscape photos used today to highlight beauty, e.g. for tourism purposes, cut out such pollution (and of course, why would they highlight that). Gill shows here just how integrated and unavoidable the pollution has become, yet depicts it in a way that still appears as a “paradise” on first glance.

Images: Pascale Marthine Tayou — Plastic Tree B [2020] / Simryn Gill — Channel #1 - #9 [2014].

Misconception.

Kazuo Kadonaga — Wood No.5 CH [1984].

As a lumber mill manager, and coming from a family of cedar forest owners, the artist is attuned to this specific material. Bark was stripped from the trunk of a cedar tree and sliced into 800 paper-thin sheets using a machine commonly used to make decorative veneers. Once dried, these sheets were carefully reassembled, returning it close to an original form. It takes a second look to realise that it is layers of wooden sheets, and so is both delightful to behold and also disarming as a reference to commercialisation.

Hugh Hayden — Zelig [2013].

Another one to take a second glance at, is these logs, one of which is covered in grouse feathers yet resembles bark. In a way it’s commenting on biomimicry. The artist remarks that “feathers and hair and skin and tree bark” are “organs of identification” and here this work begs us to question what we’re looking at.

Images: Kazuo Kadonaga — Wood No.5 CH [1984] / Hugh Hayden — Zelig [2013].

Illusion.

Kirsten Everberg — White Birch Grove, South (After Tarkovsky) [2008].

Again I have a close-up rather than the full painting, probably because I was enamoured with the textures. It’s oil and enamel on canvas so had a dreamy shiny quality. Even as a close-up you can picture the birch grove it’s based on; the way the dappled light bounces off the lustrous bark, and how the vertical lines create an illusion of depth and also two-dimensionality.

Yto Barrada — Terrain Vague - Tanger (Vacant Lot - Tangier) [2001].

This is a tower block, but with the height and irregular horizontal dashes of brown, it holds an air of birch tree about it. The whole thing actually doesn’t make sense to my eyes. It’s illusory, and captivating because of it. It seems that playing with abstraction and pattern is central to Barrada’s work.

Images: Kirsten Everberg — White Birch Grove, South (After Tarkovsky) [2008] / Yto Barrada — Terrain Vague - Tanger (Vacant Lot - Tangier) [2001].

I’m unconvinced these were the only photos I took during the exhibition. I have a memory of the main exhibition entrance, where distillation vessels were attached by tubes to a tree. I can’t find mention of this in any previous reviews, but also can’t figure out what other Hayward exhibition this was from [aha! P.S.! When linking other articles below, I realised this piece was from Dear Earth]. I take photos during exhibitions in order to look back as a form of journalling; due to the way my own memory works, I can imagine the sensations of the viewing moment. So I’m disconcerted that I’ve got this image in mind and can’t place it. Perhaps that suits, because often forests look the same; part of their charm and inducement of fear.

I found online images of other works from this exhibition that I remember being drawn to, and have additionally included, though there’s still the tension of “did I actually not take photos?” and it’s only now five years later that I’m interested by the works.

Tacita Dean — Crowhurst II [2007].

A supersized photo of the Crowhurst Yew, said to be 4000 years old, has been painted (gouached) around the edges giving it a collage effect. Originally, Dean was painting out the backgrounds of vintage postcards depicting trees, leading her to research native English trees.

Toba Khedoori — Untitled (Branches I) [2011-12].

An oil work on waxed paper that, in a similar vein to Dean’s, is hyperrealistic and jumps off the page, because of the white background (which must be indicative of snow).

Images: Tacita Dean — Crowhurst II [2007] / Toba Khedoori — Untitled (Branches I) [2011-12].

Ugo Rondione — Cold Moon [2011].

An aluminium cast of an ancient olive tree, coated in white enamel, as part of a series of twelve, all from trees between 1500-2000 years old. I wonder if the title is to do with the December full moon known as the “cold moon” or even Michael McDowell’s novel Cold Moon Over Babylon (1980), which is a bit of a supernatural horror.

Zoe Leonard — Untitled [2000].

Bark of a tree in New York City is subsumed by a metal link fence. Others in the series include barbed wire. It speaks of destruction, that us humans have contained another living being preventing it from growth, but what I’ve heard recently during an orcharding course is that a tree wants to be a tree; we’re not in control even when we think we are.

Images: Ugo Rondione — Cold Moon [2011] / Zoe Leonard — Untitled [2000].

Jennifer Steinkamp — Blind Eye, I [2018].

Even now, looking back, I can’t pinpoint if this is a digital illusion or real. I think it goes through the seasons so the leaves change colour and fall. This artist has other plant and tree-based video installations that feel hyperreal.

You can watch a 2 minute video here.

Eija-Liisa Ahtila — Horizontal – Vaakasuora [2011].

Another video installation, this one of a cinematic portrait of a 30-metre-high spruce tree, laid landscape view so that it fits in the screen. She explains that it was filmed on a windy day, helping you appreciate the aliveness of the spruce, and shown in 6 parts to give the scale — but also that in Finnish language, kuusi means ‘six’ and ‘spruce’.

You can watch a 1:32 film of the artist explaining the work.

Images: Jennifer Steinkamp — Blind Eye, I [2018] [Source: Fad Magazine] / Eija-Liisa Ahtila — Horizontal – Vaakasuora [2011].

Abel Rodriguez — Terraza Baja [2018].

I recall the joy of this. Simple in the sense of the depiction and markmaking, and vibrant, but lots to look at. It was displayed with another by its side — Terraza Alta II — I think at the top of the stairs. I wonder on reflection if we were moving up into the canopy, from the rootier works of the ground floor. Without the story, it is indeed a cute painting of a forest; but the story is that the artist, Abel Rodriguez, is an elder of the Nonuya people, who live on the Cahuinairi river in the Colombian Amazon. He learned everything he knows about plants and animals from his uncle, and taught himself to draw. In the 1990’s, he and his family had to leave the region due to armed conflict, but he continued to make images of his forest home, showing the landscape in different conditions and at different times of year.

Anya Gallaccio — Because I Could Not Stop [2002].

I can’t remember this piece, and no photos, but looking through other folks’ blogs I see this and appreciate it. It’s a bronze cast of a living (but condemned?) tree with a centre of red ceramic apples, sat in the centre of a scorched floor (which also seems to be metal). Perhaps due to the years since visiting this exhibition, where I’ve become a skilled gardener with understanding and experience of pruning and tree management, I’m more attuned to this narrative. The cultural, spirutual and religious associations of the apple, and how a fruit tree tends to be cultivated rather than natural. Here it sits completely pruned with the fruit as a reminder and a burden, not yet eaten.

Images: Abel Rodriguez — Terraza Baja (detail) [2018] / Anya Gallaccio — Because I Could Not Stop [2002] [Source: Rowley Gallery].

All photos were taken by me at the exhibition, apart from those towards the end, which come from the artists’ website unless otherwise stated.

Read similar reviews + THOUGHT posts, such as:

Dear Earth: Art and Hope in a Time of Crisis.

Mother Goddess of the Three Realms.

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art.