London Craft Week 2022.

London Craft Week is a yearly event that brings a “programme of events celebrating exceptional creativity and craftsmanship from around the world”. Unfortunately I hadn’t seen any advertising and don’t put these things in my calendar, so I missed a lot of exhibitions and workshops, but one thing I could make on a rainy day, was an open exhibit at Mills Fabrica.

Mills Fabrica is a “go-to solutions platform accelerating techstyle and agrifood tech innovations for sustainability and social impact”, and they had some innovations on show at a building in King’s Cross. This blog post takes a look at the incubatees that were exhibited.

First up I want to point out that I was not in the mood to talk with anyone. It was a drizzly grey rainy day, I was hot and bothered, and I simply wanted to look at some stuff. Ordinarily I’d have conversations to better understand the project, yet for this exhibition all I went in with was a critical mindset. So, the blog below is just that - critical. In hindsight I have given some pros for the innovations, so I’m not fully disregarding them, but from the perspective of my own set of values, (most of) these products just shouted out “stuff” to me.

Modern Synthesis

Touting themselves as a “biomaterial innovation company”, Modern Synthesis are working on biofabrication technologies to reduce fashion’s demand for petrochemicals. They use robotic machinery to “weave” a pattern of yarn that microbes then grow around, so creating a material - or often the full shape of a product - that is part human-made and part microbe-made.

It eliminates cut-make-trim waste common in factories, and indeed labour costs (and associated ethics), because the product can be made to specification and with only the weaving arm machine and the microbes. But then, what are the ethics with this? I guess, microbes are there simply to eat and poo and eat and poo, so if you’re providing this then perhaps it doesn’t matter what the setting for them. And yet, in eliminating a large proportion of people from the production equation, you’re also reducing skilled jobs - and we like to think that the job sharing economy will work, however it’s not necessarily practicable in exploited nations where a lot of fashion is produced. So then what employment will they have?

The argument against not using petrochemicals for fashion is a solid one, especially when we don’t have the working recycling infrastructure required to build any dream of circularity. Though what I find with these biomaterial innovations is that they negate to tell the story on where the underpinning raw materials come from - Modern Synthesis highlight the microbes, but they’re not saying where the cellulose for the yarn comes from. If it’s not organic, then petrochemicals are being used for fertilisers and pesticides, and likely in production too. Even if they’re using a recycled cotton source for instance, it can still have been a non-organic cultivation. And most often, petrochemicals are the energy driver too.

Pros ⇾ Could eliminate production waste / Presumably fully biodegradable without much repercussion to soil health (maybe even beneficial) / Nice looking material / Fair amount of application in the luxury world

Cons ⇾ Where do the other raw materials come from? / What about the energy involved for the lab? / The ethics of controlling microbes, and they even point to developing research in genetic engineering / Reduces human employment at scale / Not accessible to all

Eugène Ricconneaus: ER (Solier)

Shoemaker Eugène Ricconneaus has created his own blue pigment from ocean waste and then used this mixed in with certain materials for a womenswear sneaker collection currently open for crowdfunding. Along with the ‘earth pigments’, he also designed the shoes to use different ocean materials: fishnets for the soles, seafood (which seems to be shells) for the upper pads, seaweed for memory foam inserts and “ocean plastic” for laces (plus cork, recycled rubber, unused leather offcuts, recycled EVA).

All in all I’m just like, yeah, you’ve thought about the materials you’re using, but what about the design itself? You’ve just designed yet another trainer that yet again can’t be disassembled easily for repair. It’s a combination of natural and synthetic, whether recycled or virgin, and what are the ocean plastic sources anyway? Creating a shoe that can just as well become ocean plastic is not a solution. Fair enough that it has been designed for a specific audience (skateboarders), and that it has been assessed for its carbon footprint, but why not educate a little more in the process.

Pros ⇾ Interesting materials

Cons ⇾ But these materials are not fully explained (“seafood”?) / The shoes can’t be disassembled / They’re polymaterial.

Flax London

I’m a fan of Flax London, only really because they exclusively use linen, not that I’m a customer (it’s menswear focussed so the fit probably not right anyway). Ok so they need to use cotton for the garment labelling, and probably corozo nut for the buttons, which unfortunately they don’t tell you - just that they don’t use plastic. But it’s great that they are sticking to their guns and showcasing linen as a year-round fabric. They also state what mills they source their linen from, something fashion brands hate to do for fear of competitors. This shows that the brand really are happy if more folk use linen.

I would say that they could use their platform to educate more. And it’s always the same retort about cotton using more water, yet the statistics cover total cotton rather than separating out rain-fed organic, for instance. They’re not particularly showcasing the wonder of the traditional production methods that they say the mills use, either. To the exhibition’s credit though they did have a reel of raw yarn and some processed fibre so visitors could have a feel, yet for me doesn’t go far enough to explain the varied applications and cool seed-to-fibre fun of flax.

Pros ⇾ Advocating for one fibre gives brand purpose / Educating consumers on alternatives

Cons ⇾ It’s not particularly changing the system or one’s desire to consume

Fanfare

So, according to the information banner for clothing label Fanfare, they are “leading the recycling movement” by using unwanted materials. I don’t know if this is Fanfare’s copy or Mills Fabrica’s copy - but this project/business has nothing to do with recycling. This is about there being too many items already on the market, either discarded by consumers or overproduced, and then utilised generally as is before being dumped anyway. Recycling is a process by which the discard can be shredded and transformed into something else. You may be helping with the repurposing movement, but it’s arrogant and deceitful to be saying that you’re doing something about recycling. It’s the miscommunication that gets me - even on their website the product descriptions say “recycled jeans” for repurposed items, when “recycled” jeans would ideally mean that the fibre itself is recycled. They’re not ‘re’ cycled: they’re just cycled into another part of the system as they are.

What they’re actually doing is taking unwanted ready-made clothing and arty-ing it up, with paint and embellishments. So they are creating unique pieces that yes will prolong the lifespan of it, but it isn’t solving the lack of recycling infrastructure, or designing to make recycling easier, or even in fact educating on what repurposing and recycling really means.

Pros ⇾ Cool one-off garments repurposed from clothing discard

Cons ⇾ Communicating incorrectly / Simply prolonging rather than addressing the cause

Unspun

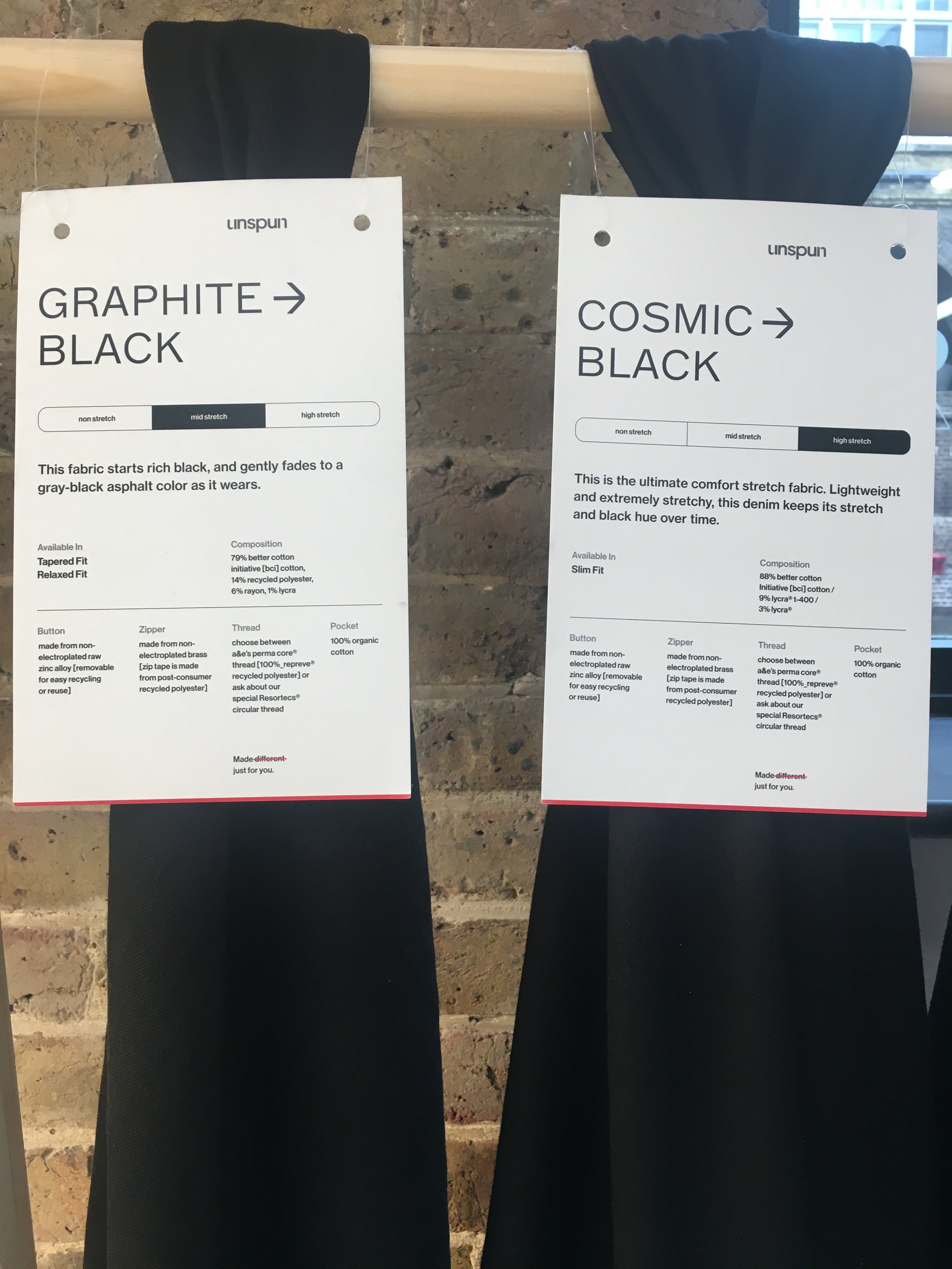

Unspun is a jeans brand creating “on demand” pieces, meaning that nothing is made until a customer places an order, and a 3D weaving machine produces the garment. For an item as complex as jeans, I’m intrigued how one machine could do all the work. The made to order model eliminates overproduction that brands consistently do because it is difficult to know if something will be popular or not (even though analysts will comb through previous sales reports, trends, and merchandising will get involved with price reductions if stock still exists at the end of the season). Brands concerned about overproduction will do exclusive drops or work with this bespoke model, unlike brands such as H&M known for burning and slashing overstock.

What troubles me, is that the effort gone into building such a techy model is lost when you produce denim fabric in an unsustainable way, as shown in the images of fabric hangers. BCI cotton is a controversy in and of itself, but then using recycled polyester, Lycra® and rayon in one blend then simply means the fabric - with current infrastructure - won’t be recycled to any similar value. Even anticipating the customer will hold and use the jeans for decades, and by then recycling will have improved (where fibres can be separated and re-used), there are still issues with rayon (which is also viscose, by the way). One fabric uses Lycra® T400®, which is actually a recycled polyester and bio-based elastane, but still, elastane breaks down easier with washing and sunlight than say cotton, so diminishing the life of the jeans through that simple decision to use a blended fabric.

They do have a purchasable collection with Pangaia fabrics, so that’s a nice collaboration, and in the material science world, Pangaia are pulling out all the stops to develop substantially sustainable textiles. Yet, even within these products there is no explanation about how they do the washing (where you give the denim an aesthetic treatment), though they’re constantly giving statistics on how much water and energy they’re saving. It overall feels like they could’ve pushed a bit more to make it groundbreaking.

Pros ⇾ Should eliminate waste with the custom fit (but no evidence that the fits satiate the consumer need to not buy more jeans), and means you can have a variety of fit options (but someone still technically has to sample)

Cons ⇾ Fabrics, though working towards “better”, could have had more lifespan thought put into them

Urban Fungarium

A neat interior thing, the Urban Fungarium products are various fungi substrates in hard perspex balls that can be hung in your house via macramé hangers, or otherwise acoustic panels grown with the help of mycelium. They smelled like mushrooms and that would be pleasing enough for me, yet they are also fun to look at and can be nurtured like plants, along with utilising home “waste” materials as the substrate. The main premise is to educate consumers on the benefits of biophilic design (reconnecting with nature through the materials in your built environment), with the Urban Fungarium actually being a platform for mycological conversations where cool design can spark new experimentation.

Some of the photos I snapped showed mushrooms similar to oyster, so potentially you could be using these orbs to grow your own food provided you select an inert spore and have a clean mould-free house. I guess founder Rachel Horton-Kitchlew’s platform would help you decipher what was possible. I like that these are conversation pieces and fairly low impact.

Pros ⇾ Low impact conversation starter that would be fun to use and nurture / Alongside the platform it can be a source of inspiration for designers looking to transform the systems in their practice / Working to learn and understand

Cons ⇾ Don’t really have one apart from considering where the perspex comes from and where the orbs are made

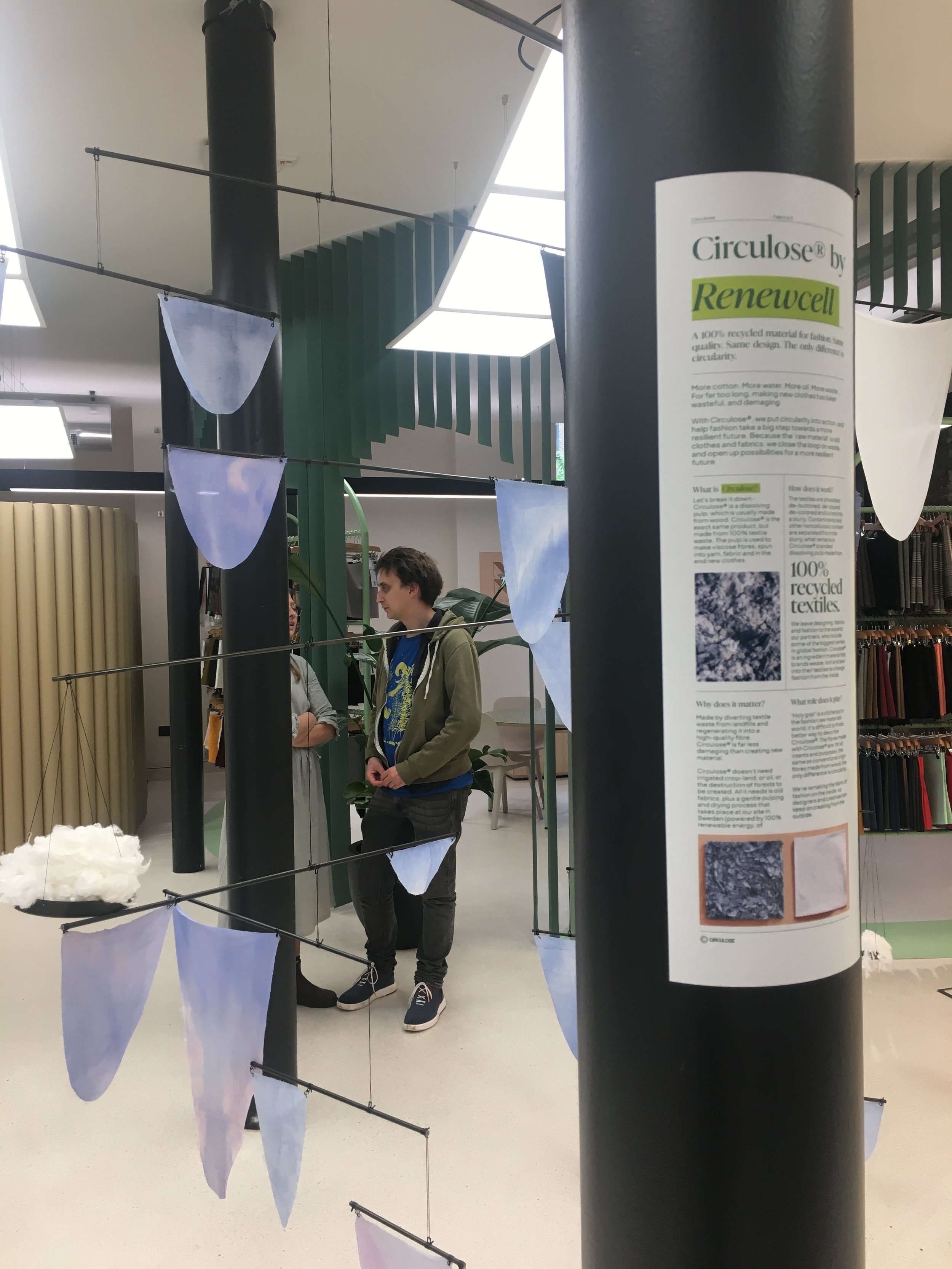

Re:newcell

There is investment from fast fashion retailers into solutions that essentially allow them to carry on producing because there’s seemingly a “get-out-of-jail-free” card. The Circulose® project does fall in to that category, and in this instance I’d say it fits as it’s a Swedish company and there’s one particular Swedish fashion conglomerate calling the shots in high street clothing. However, investment does mean a quicker hit of R&D, and therefore the re:newcell group - the material scientist group behind this project - have been able to produce a regenerated cellulose fibre that has been used in clothing already (by the retailers invested in the project).

They take old clothing, take away the components (don’t know what happens to these), shred the textiles, turn it into a fibre slurry (presumably with solvents), make sort of fibre “paper” pulp sheets, and this is then spun into new fibre. They do state “hopelessly out of style” clothing is used too, which maintains the premise that stock comes from unsold overproduced items. Additionally, the secret process of course is never given away (Circulose is a registered trademark), so you never know what is used to break it down - but anything regenerated has to have the polymers stripped, and solvents is really the only way to do that. They say it’s a loop, and so it’s presumptive that all solvents and water are part of this loop too (especially as they claim to use 100% renewable energy - it is produced in Sweden after all), but trade developments are unlikely to be shared, and to a large extent because the key stakeholders are fashion businesses wanting to have an edge for their sustainability campaigns.

Pros ⇾ A tried and trialled regenerated fibre from what would otherwise go to landfill, be exported, or incinerated.

Cons ⇾ Secrecy over the full method so we won’t ever know the ingredients list, but at least should be under strict EU regulations (and they never state that it’s a natural fibre, so no miscommunication) / It perpetuates the cycle of overproduction because there’s a solution to use up the excess

Colorifix

As someone who enjoys the natural colour plants give, it’s difficult for me to see the benefit of “growing” colour in a lab. Yes, synthetic dyes come from labs anyway, but at least you know it’s fake. Bacterial and engineered dyes, whilst cool, are still controlling something that normally has a life of its own, and I don’t recognise this as sustainable. If it gets to a point where we need to start from scratch, for example rebuilding depleted food systems and reigniting land-based artisanal enterprises in the wake of a climate catastrophe, then how is growing stuff in a lab going to help us? Efforts should be going in to remembering and respecting indigenous wisdom and working with this knowledge, rather than constantly relying on control and making something work to our whims.

Ok, so Colorifix use DNA sequencing to identify the pigment-producing gene within plants (without ever touching a plant), and then they “translate” that code into their microorganism - changing what the organism was set to do. The microorganism then creates the pigment “just as it is produced in nature”, except without ever touching nature, it is fed on “renewable feedstocks” such as sugar, yeast, and plant byproducts, to create a dye liquor in a couple of days. This then goes into normal dye machines. So yes, it’s quick, it’s scalable, you can get a plethora of colours without using land for the pigments, but you’re still brewing the liquor requiring land (that could be used for food) for the fermentation feedstocks.

Why not simply grow dye plants that can also be food, that can be interplanted with food, that are regenerative through nature of them being perennial rather than needing to be pulled up on an annual basis? And you’re still not doing anything to curb the overproduction because again you’re saying it’s ok, we have a quick solution. And you’re still not doing anything to educate on where colours come from and why pigment exists in the first place, because you’re retaining that lack of connection between plant and humans.

Pros ⇾ Petrochemicals not (necessarily) used in the process to make synthetic pigments / Limited toxic substances in the textile industry / Less land required than natural dyes / Wide range of “natural” colours available to the textile industry

Cons ⇾ No opportunity for regenerative practices / No education / Very easily reducing accessibility through intellectual property / Requires a lab / Controlling microorganisms

V-Farm

I’m a food grower, in a permaculture kitchen garden with forest garden section, so soil is incredibly important to me. It should be important to you too. I recognise that there is a place for vertical farming using minimal soil, or otherwise hydroponic systems, in places where land access is an issue, or heavy droughts or heavy rainfall causes too much chaos to grow food effectively. But I also just think that, as with a lot of projects above, it’s a backwards step to the systems mindset we need. We can’t just shove plants indoors and expect them all to be happy. The plants on show here were clearly scorched, probably from the LED lights, and frankly it makes me sad. Ok, this is what V-Farm say:

At V-Farm we believe the answer lies upwards. By farming vertically indoors we can reduce the need for agricultural land, focusing not on warehouses, but on disused inner-city buildings & growing underground or within the retail / living / working spaces. This not only reduces the distance produce travels to the supermarket shelf but also promotes social enterprise and interaction. We can also raise production in existing farm infrastructure through smart propagation systems and speed up research with multi-level fully controllable research units.

To me, as an urban grower, we can achieve food security anyway using disused spaces, existing farm infrastructure and “smart propogation systems” - it’s all about skill sharing and local wisdom. And by working in a community, by building knowledge from the ground up, we can have security as ourselves, not through needing to rent out space or equipment. Granted, V-Farm do seem to be focussed on creating efficient spaces that are about food not tech, but I didn’t see this with the installation at Mills Fabrica. Again, my poor mood won’t have supported considerate conversation, but I believe that the only way I’ll truly understand these systems is to go trial work in them.

Pros ⇾ Can be installed in unused spaces and they tend to be efficient with water usage / Presumably no need for pesticides and fertilisers, though they don’t state they’re organic

Cons ⇾ In no way is growing plants indoors beneficial for anything but greedy humans: where is the security in growing indoors losing traditional wisdom and continuing land to be used by wealthy landowners only?