Rethinking waste (farming + trade).

The Food: Bigger Than The Plate exhibition at the V&A Museum in 2019 regarded different elements of food; I have already covered the opening (composting) and closing (eating) sections of the exhibit, and here I’ll uncover some parts of the in-between sectors: farming and trade.

Read part one of the blog on Rethinking Waste here in the food and materials article.

Farming.

Farming shifted towards industrialisation over the last 200 years as machinery, inputs and labour became more readily available and cheaper. And though we rely on farms and farmers to sustain us with food, only 1.5% of the UK workforce works in agriculture. Does this mean that farming actually does not require so many workers here, or that our food is farmed by migrants who don’t come into these statistics? Or perhaps that we simply import most of it?

Small-scale farming is increasing - not for popularity, because the difficulty of purchasing land to do so is nigh impossible - but as a more efficient and transparent way to achieve food sovereignty. So those who believe, will try hard. However, whatever the farm size, it seems to be that farmers struggle through regardless; because of a land legacy, because of a need to steward… and since this exhibition was curated, the UK has undergone massive change due to Brexit making it even harder to achieve profit from this way of work. And still we come back around to the fact that we cannot survive without food producers.

“The world already produces enough to feed 10 billion people. A third of this food - 1.3 billion tonnes every year - is wasted.”

Ok, so I made notes on particular works that spoke to me, and have put them - along with some additional projects from the exhibition book - into sections: technology, agrarian knowledge and urban farming, and education (for farming), and local food design, traceability, understanding science, and shipping (for trading).

Technology.

“The unsung reality that the world is currently producting enough food to feed 3 billion more people than are alive has come about largley through remarkable advances in agricultural technology. New varieties of crops, GPS-guided precision sowing and fertilizing and hi-tech farm machinery have all contributed to enormously higher yields. / This abundance would astonish our ancestors.” ~ ‘Rewilding’ by Isabella Tree (page 135).

l’Atelier Paysan

l’Atelier Paysan is a French-speaking collective of small-scale farmers, employees and agricultural development organisations, gathered together as a cooperative offering a tool box of farmer-driven technologies and practices.

“Based on the principle that farmers are themselves innovators, we have been collaboratively developing methods and practices to reclaim farming skills and achieve self-sufficiency in relation to the tools and machinery used in organic farming.”

Mainstream agricultural research is increasingly oriented towards proprietary technology in service of large-scale monocultures over small resilient agribusiness. Collectives such as l’Atelier Paysan (and Farm Hack in the US) are connecting farmers with designers, engineers and thinkers to develop and share tools that will benefit those who intend to use them, rather than those simply intent on selling them. They are merging the hacker/maker movement with traditional farming skills to ensure a regeneration of resources; what is exceptional is that all resources are then open source, so you can download technical drawings and tutorials from their website.

MIT Media Lab Open Agriculture Initiative (OpenAg)

The Personal Food Computer, designed by a range of educators from across the US, enables “nerdfarmers and newcomers alike build for a wide range of scientifically rigorous, citizen-science experimentation”. It is a 3D printed box with open source making and assembly instructions that provides a closely monitored space for growing. While it is completely over the top for your everyday growing, it does open up research and experimentation to the everyday citizen as “controlled-environment agriculture”. There is an article from MOLD that gives a complete overview of the platform and outcomes.

Project Florence

Artist in residence at Microsoft, Helene Steiner developed Project Florence to highlight the communication we have with our natural environment through a reactive rudimentary conversation that comes about by attaching electrodes to plant tissue. “Plants synthesize a very large amount of information via electrical and chemical signals and deliberately make changes to themselves, their neighbors and the land nearby for their benefit”. It is a cute, mostly benign comment on bridging the natural and digital worlds through computation.

After watching Little Joe, a Little Shop Of Horrors-esque creepy consideration of plant sentience, this is why I say “mostly benign”. I feel slightly that putting plants in a scenario where they’re forced to talk in our language isn’t really getting to the brunt of mindset shift required to fully embrace their importance.

Images: l’Atelier Paysan; The Personal Food Computer from MIT; Project Florence from artist Helene Steiner.

Agrarian knowledge and urban farming.

Farmers tend to be on the geographic margins and yet by bringing them into urban environments - by way of sharing their actual produce or their skills of production - then new narratives can form around what rural life is. It isn’t a remote space where nothing happens, but a place where wisdom of resilience is found, something that cities have shrunk from in the wake of convenience.

As food insecurity increases with supply chain disruptions caused by drought, floods, trade and labour, the more that small-scale food production is required.

HK Farm

Artist collective HK Farm occupied rooftop spaces around the city (a place that regularly ranks as number one in being the most unaffordable in city living) and worked with farmers evicted by development projects from the New Territories. In this way, marginalised communities are able to resist economic corruption that is forcing them off their land into supermarkets.

HK Farm can’t be found online now, but Rooftop Republic could be, so perhaps it has purchased. Rooftop Republic seems to operate as a manager of all urban growing spaces around Hong Kong.

Company Drinks

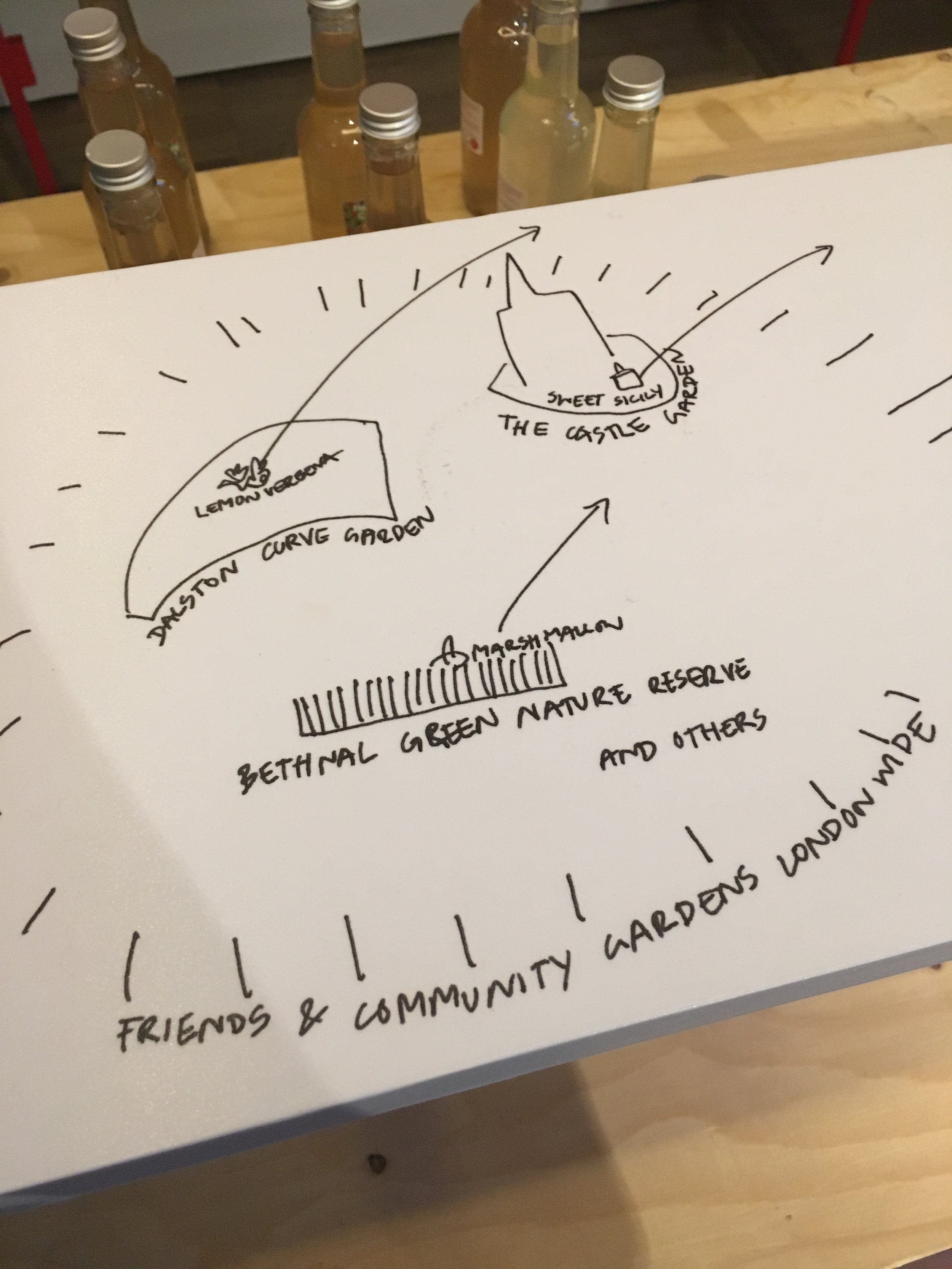

Drawing upon the “hopping” tradition of urban dwellers into rural spaces to forage and collect food, East London enterprise Company Drinks invites local residents to preserve their ancestral heritage through picking trips. The produce is transformed into seasonal drinks outside of a capitalist framework, with educational programmes, a community economy, and a collective desire running the show.

DIY food efforts

The Second World War was a time of community spirit, in a sense, because everyone was called upon to farm and grow for “the good of the village”. One such poster highlights the importance of food in a time of war, moreseo perhaps than ships; people can’t fight if they are not fed. This sentiment is coming to the fore again today in demand of seed sovereignty. Yet, another perspective is about farming every single scrap of land because that’s just the way things should be.

“The notion that we must work every inch of the land for our survival, ingrained in us since the Second World War, is highly emotive, and distressing images of famines in war-torn and politically unstable regions of the world daily reinforce the idea that there is not enough food to go round. / But this message does not reflect the experiences of farmers like ourselves, driven out of business by the global market - by low commodity prices resulting from subsidies and over-production.” ~ ‘Rewilding’ by Isabella Tree (page 132).

Fallen Fruit

I am writing this in 2022, way after the Food exhibition, but caught in a Cost Of Living Crisis due to energy price caps and rising inflation. There are fruit trees all over, and despite a lot being on privately-owned land, there is a community spirit brewing to allow gleaning to occur - both to save the mess of windfall, but to share out the goodies. Fallen Fruit is led by artists David Allen Burns and Austin Young who use fruit “as a material for interrogating the familiar” by investigating “interstitial urban spaces, bodies of knowledge, and new forms of citizenship”.

The exhibition hosted some of their London maps that highlight where fruits trees grow in or over public space, and are ripe for the picking. Imagine if this could be shared within neighbourhoods to avoid waste and to promote foraging.

“From their work, the artists have learned that “fruit” is symbolic and that it can be many things; it’s a subject and an object at the same time it is aesthetic. Much of the work they create is linked to ideas of place and generational knowledge, and it echoes a sense of connectedness with something very primal – our capacity to share the world with others.”

Images: Rooftop gardening in Hong Kong, from Rooftop Republic; Company Drinks historic hop-picking “hopping” day out (brother Terry and mother Ellen); the Use Spades Not Ships poster, from Imperial War Museum collection; Fallen Fruit map of London locations from artists David Burns and Austin Young (photo taken by me during the exhibition).

Education.

Our Daily Bread

This feature length film from Nikolaus Geyrhalter is an uncommentated look at the world of industrial food production and high-tech farming across Europe. It is harrowing and enlightening, taking the viewer on a harvest and processing of such industries as spraying sunflowers with pesticides, salt mining, cauliflower bagging, the scale of cucumber production, cow fertilisation for milk, fish skinning and apple picking. Because it isn’t narrated, the sounds are all-encompassing. At the V&A exhibition, there was a small area trellised off where everyone sat closely packed watching a small screen; this added to the discomfort of what you were watching, even when it was as benign a staff worker eating their lunch.

Studio Nienke Hoogvliet Bare Bones

The material researcher Nienke Hoogvliet and her studio explored the bone china industry, and whether today’s industrially-farmed animals are suitable for such a material. Subsequently, the Bare Bones project is an ongoing research project that compares the qualities of different types of bone derived from both organic and bio-industrially kept animals and how they function when produced from ash into bone china. Such research educates on the wider supply chain and economies affected when farming quality is reduced, along with supposing that the quality of the china reflects the quality of the animal’s life.

Planetary Community Chicken

I was frankly drawn to this one because of the close-up chicken portraits. But Belgian artist Koen Vanmechelen has been cross-breeding chickens from different countries since 1999 for project Planetary Community Chicken (PCC), creating a collection of chickens with genetic diversity that creates translocal nutrition and income, so it’s bigger than just some fun photos of perturbed chickens.

“The introduction of a new ‘cosmopolitan genome’ to the local flock puts an end to the ongoing cycle of genetic erosion that results from local inbreeding and industrial highly efficient mono-cultural production. It promises greater resilience and adaptability. In turn, the local chicken provides familiarity and the necessary characteristics suited for the local environment, as well as resistance to domestic threats.”

Images: 1. “Our Daily Bread” film still; 2-3. Studio Nienke Hoogvliet comparison of organic to industrially-farmed bones, and examples of bone china made from those animal bones (3 was taken by me at the exhibition); 4. Koen Vanmechelen “Planetary Community Chicken” breeding programme.

Trading.

“The modern food system has entangled the planet in a web of complex journeys, transactions, relationships and processes. Yet most of this vast, all-encompassing system is invisible to the average human. Hiding in plain sight, in our everyday activities of shopping, cooking, eating and disposing, this system is one with which we interact daily, maybe even hourly. But most of us cannot in good faith say that we really understand how it works.” ⇾ words from the FOOD: Bigger Than The Plate exhibition book (page 72).

A quote in an interview with Brewster Kneen of Share International, ‘From Land To Mouth’ (1994), says:

“Food is a commodity, a way of making money. Feeding people is simply a by-product of the system’.

And this feels like it stands true today when land is used moreso for growing crops to turn into bioplastic or animal fodder than it is to actually feed people. Especially when we take into account the ecological and social effects that industrial farming has on its own, food production is not sustainable - it’s simply economical. It would be interesting to see an update of this exhibition post-Covid 19 pandemic and Brexit.

By understanding the supply chains that bring our food, recognising the folk/animals/plants/resources involved, and turning attention to the advertising that makes food a commodity rather than a need, we can begin to register how our citizen voices can make systemic change. As seen above with alternative farming methods, so too do we need a shift in the way we trade - this is why I believe an update following two major global events would further the insight.

Local food design.

Designing food and trading in a way that serves the local economy and cultural needs is not only supporting preservation of wisdom and skills, but reducing waste and improving resilience. Such projects include:

⇾ Company Drinks, as mentioned above

⇾ sulsolsal Cerveja de Abacaxi pineapple beer

⇾ Raw milk vending machines across Europe for direct-to-consumer sales

Plus all of the byproduct materials I highlighted in part 1 of this article, including Vegea grape leather, Ecovative mushroom interiors, and Kaffeform’s coffee ground waste cups.

One way to make hyperlocally-designed food that can be doctored to suit another’s locale is by ensuring open source information and instructions. In this way there is the sharing of local wisdom, yet with inspiration to look at ingredients in one’s own environment; this enables local trade from local knowledge, but on a global scale.

Cube Cola

Cube-Cola is one such operation (originating in 2003 out of Cube Cinema in Bristol, UK) that is resisting the secrecy of well-known branded products and the proprietary knowledge that comes with it, into one that is open source and fun. Their cola recipe was reverse engineered from analysing Coca Cola over a two-year period, and is now sold as a concentrate to such makers as Company Drinks above - or to individuals. You can access the open source Cube-Cola recipe for free, or purchase the concentrate.

Images: Cerveja de Abacaxi pineapple beer with 19th century printing press to print the bottle labels; a raw milk vending machine, image from Modern Farmer; Cube-Cola’s cola concentrate open source recipe; Company Drinks map of ingredients (including from The Castle, which is where I work!).

Traceability.

Jaffa Orange wrappers

Fruit was traditionally wrapped in printed tissue paper to protect the fruit from mould during transportation, and was utilised as a way to essentially brand a country. As shown by the photo below of exhibition information placards, the retaining of these wrappers gives a glimpse into how nations brand their product. They are also an artefact of the current state of refrigeration required, or of breeding and pesticide use, because tissues would only now be present for a luxury organic and fresh product.

Provenance

Provenance is a technology software company that transforms supply chain data from all sorts of industries into credible shopper-facing communications. Their framework covers all of the phrases you come across with sustainability and ethical credentials, but use an “Integrity Council” as the third party so businesses aren’t judging their own actions.

You’d expect it to be highlighting blockchain technology, but this word is nowhere to be found. While in 2019 when the exhibition was on Provenance was new and intriguing, with QR codes that gave you insight into each element of the product, these days it feels like more lip service, with the platform being a place to create content for communications rather than the actual supply chain monitoring itself. Though there are verified checks that can give customer assurance, it isn’t really removing any of the confusion or improving supply chain ethics, because data is still manually updated? It’s unclear, and this doesn’t feel like traceability or transparency.

Images: 1. Taken in situ at the exhibition; 2. 'Griechische Oranges. Prinz von Kreta', fruit wrapper, 20th century, Italy. Museum no. E.1704-1974. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London; 3. The Provenance exhibit at the V&A; 4. Provenance customer-facing app.

Understanding science.

Edible Geography/Gastropod

The Edible Geography blog and associated Gastropod podcast from Nicola Twilley highlights the history of food, from food packaging to food waste to food misconceptions, through the lens of science. The blog is now not really updated but there is an archive, while the podcast is fresh every two weeks. I don’t know now why in particular this was highlighted at the FOOD exhibition, but I made a note on it so it must have had some impact.

Selfmade

The Selfmade project, from scientist Christina Agapakis and scent expert Sissel Tolaas, challenges attitudes towards bacteria by creating a ‘microbial portrait’ of the donor; bacteria is taken from people’s ears, toes and armpits and used in the creation of cheese. The ones shown at this exhibition were remade in London by Helene Steiner with the help of the biotech startup lab Open Cell.

Black Pudding Market

With science comes the need to question ethics. One such project does that, and in fact could not be produced in full for the V&A exhibition due to legalities. John O’Shea’s Black Pudding Market questions if vegetarians would eat black pudding if it came from a live animal rather than a dead one (it wouldn’t for me, the texture and smell would be enough to put me off). O’Shea’s research led him into the legal grey areas to explore the purpose of animals in our food supply chains; rather than being hosts, could there be a symbiosis in this commodity? Frankly I can’t see the benefit, and don’t really understand at what point we’d be taking blood from a live pig anyway?

Shipping.

“In developing countries food tends to be lost at the front of the food chain, rather than at the end. Poor infrastructure - lack of refrigeration, transportation, storage, food-processing plants and communications - equates to a loss of 630 million tonnes, almost the same as in the developed world.” ~ ‘Rewilding’ by Isabella Tree (page 134).

Growerame

Due to an imbalance between imports and exports, every year 26.1 million shipping container loads travel from China, but only 12.9m loads travel back to China – meaning that half of the containers going back to Asia are empty.

Innovation Design Engineering graduate Philippe Hohlfeld stumbled upon this fact after eating a banana and wondering where it came from, so he decided to map out all of the world’s shipping routes. The solution was to house a vertical farm within the empty shipping containers so that there was an efficient use for the journey. Back in 2016 when Hohlfeld had developed this concept, it relied on the designer doing the unloading and harvesting of the farms himself once they reached their destination - it’s uncertain if he managed to sell his crops to retailers in the Chinese food market as a luxury item.

Images: 1-3. from Philippe Hohlfeld for GrowFrame; 4. taken at the V&A exhibition to show model shipping container.

Banana Story

Johanna Seelemann and Björn Steinar Blumenstein developed the Banana Story project to expose the banana’s hidden journey. Banana Made-In Label is an illustrated label that shows the journey a banana takes, while Banana Passport is a tongue-in-cheek artefact of that journey, perhaps that the banana hands over to its eater. They follow the journey of a banana from Ecuador to Iceland: 12,534 km in 30 days on a cargo ship, passing through 33 different pairs of hands.

Images: all from Johanna Seelemann from Banana Story.